What is IBD?

IBD or Inflammatory Bowel Disease is an umbrella term for all of the inflammatory diseases affecting the gastrointestinal tract. The common diseases classified as an IBD include ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, microscopic colitis, and indeterminate colitis. The gastrointestinal system has to absorb vital nutrients, water, and other chemicals while simultaneously protecting us against pathological microorganisms and toxins. There are many ways this system of determining good vs bad (and keeping the bad out) can become maladaptive.

The bowels typically become inflamed as the system responds incorrectly to the gastrointestinal threats, and is unable to prevent them from being absorbed through the intestinal wall. Occasionally, disruptions to the bowels will not cause chronic inflammation and subsequent ulcers, but still cause functional issues and distressing symptoms. This is referred to as IBS or Irritable Bowel Syndrome. It is important to take note of the difference between these seemingly similar conditions. The focus of this discussion will be on IBD. However, IBS is frequently benefited by some of the same techniques for managing healthy sleep patterns.

What Factors Influence IBD?

There are a number of factors that influence the outcome of the different forms of IBD. These include genetics, drugs, diet, smoking, alcohol use, exercise, environmental conditions, infections, hygiene, stress, and sleep. All of these factors can be utilized to better bring IBD under control. All of the factors should be considered equally important, but this article will focus on sleep. It is imperative to maximize your sleep hygiene because the average person spends approximately one-third of their life asleep! With or without IBD, the quality of your sleep will have drastic effects on your life while awake. Despite spending so much of your life asleep you probably don’t think much about it unless you find yourself desperately tired from a lack of good sleep. Like air, nobody values it until they don’t get enough.

How Sleep is Studied

Most of what is known about sleep came from observing people’s movements, breathing, pulse, blood pressure, and brain activity as they slept. A major advancement was the invention of the electroencephalogram (EEG) to measure electric activity in the brain. There are several different frequencies of brain activity that can be used to determine what is happening in the brain during sleep. The frequencies are measured by cycles per second, which are also known as hertz (Hz).

- Beta Waves (15.0-30.0Hz) – These waves are associated with being awake and alert. They have the highest frequency and lowest amplitude and can be very inconsistent. When you are anxious or focused on something these waves are predominant.

- Alpha Waves (9.0-15.0Hz) – These waves are associated with being awake but relaxed. They are slower in frequency than beta waves and higher in amplitude. They are more consistent than beta waves and are associated with relaxation.

- Theta Waves (4.0-9.0Hz) – These waves are the slowest frequency and highest amplitude before falling asleep. When you are dazed from driving long distances on a freeway, traveling by train and staring out the window, or daydreaming in class your brain is producing theta waves. They are also important for dreaming and cycling from nREM sleep to REM sleep.

- Delta Waves (0.5-4.0Hz) – These are the frequencies associated with sleeping. They are very slow in frequency and large in amplitude. In some cases of very deep sleep or unconsciousness, the frequency approaches zero hertz. Any frequencies under 0.5Hz are not traditionally considered normal, but a newer version of EEG called full-band EEG will eventually prove these ultra-slow frequencies to be an integral part of brain activity (Demanuele, 2007).

- Low-Amplitude Mixed-Frequency (LAMF) Waves – These waves are also called desynchronized waves. They consist of a variety of different low amplitude frequencies that occur when a person is connected to an EEG and actively thinking, moving muscles, or has certain health conditions. Paradoxically, they also occur sometimes during sleep despite being associated with wakefulness. Some studies have been done to determine if LAMF waves occur with any sort of pattern or if they are truly random (Ahmed, 2013).

- K-Complexes – These are waves that frequently occur in response to stimuli. They happen very quickly and appear very distinctly on an EEG, like a twitch. They are associated with a specific stage of sleep and scientists speculate they may be involved in keeping you relaxed while you sleep.

- Sleep Spindles (11.0-16.0Hz) – These little bursts of waves frequently occur after k-complexes during sleep. They are also characteristic of a specific stage of sleep and are associated with relaxation, memory consolidation, and sensory processing. They occur spontaneously and in reaction to external stimuli.

What Happens Inside Your Body When You Sleep?

To understand how you can improve your sleep and how sleep is connected to IBD; you must first have a basic understanding of what sleep is. The basic definition of sleep is a state of rest in which most physiological processes slow and prioritize repairing and replenishing. Your body completely changes how it works during sleep to perform essential tasks necessary for maintaining your ability to function while awake. These tasks include, “development, energy conservation, brain waste clearance, and modulation of immune responses, cognition, performance, disease, vigilance, and psychological conditions” (Zielinski, 2016).

There are four stages of sleep that are cycled through multiple times during a period of sleep. These stages serve many different purposes that are not fully understood, and they have distinct characteristics. One of the most significant characteristics of the stages is the presence (or lack of) rapid eye movements (REM’s). Three of the stages of sleep occur with little to no eye movement, they are called non-REM stages (nREM). The stage with rapid eye movements is referred to as REM sleep. All of these stages seem equally as important, disruption to any of them causes serious health problems.

- nREM Stage 1 (N1) – This stage is the beginning of sleep. Your muscles are not yet completely relaxed, your breathing has not yet slowed down, and your brain shifts from alpha waves to a mixture of LAMF and theta waves. It is very easy to wake someone from this stage of sleep, and it briefly lasts approximately 1 to 5 minutes.

- nREM Stage 2 (N2) – This stage occurs as you fall deeper asleep. Your breathing slows and your body temperature drops. Your brain’s activity is now all theta waves. Your brain begins to create progressively more k-complexes and sleep spindles. While sleeping you spend most of your time in this stage (Malik, 2018; Patel, 2020).

- nREM Stage 3 (N3) – You are deep asleep by the time you reach this stage. Most people are extremely difficult to wake up at this stage. The grogginess experienced from being woken up during stage 3 sleep is known as sleep inertia. Normally sleep inertia only lasts 30 to 60 minutes, but it can certainly make it difficult to fully wake up. The spaced-out K-complexes created during stage 2 eventually form persistent delta waves as you enter stage 3. In this stage, your body starts to focus on repairing itself, building new tissues, and making adjustments to your immune system. This part of sleep is very important to IBD due to these immunomodulatory effects and the need for your intestines to heal.

- REM Sleep (R) – After stage 3 you begin the REM sleep stage. Your brain is very active during this stage; almost as if you were awake. Your muscles are completely relaxed, breathing can be irregular, and your eyes rapidly move around. REM sleep is most commonly associated with dreaming.

These stages are cycled through multiple times a night. The cycle takes about 70 to 100 minutes the first time and about 90 to 120 minutes for subsequent cycles. Nobody has discovered the reason for the specific amounts of time spent in each stage and the lengthening of the sleep cycles as sleep progresses. With further research, the complex organization and purpose of the architecture of sleep will be better understood. With a better understanding of the nature of sleep, we can develop new ways to improve it.

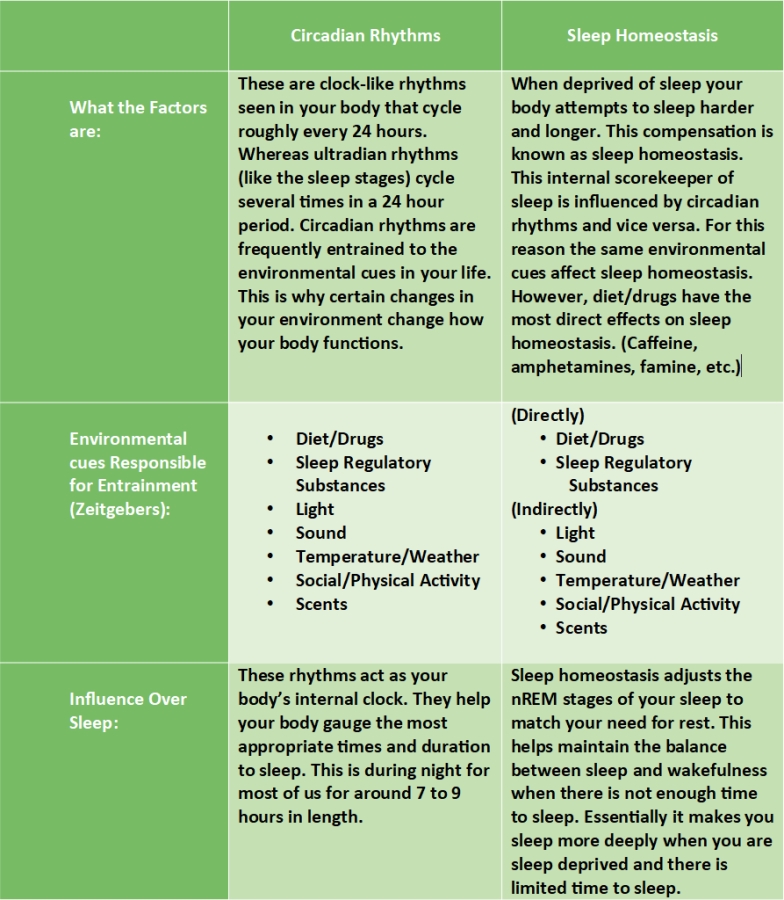

Although we do not know the function of the specific time patterns seen during the sleep cycle we do know there are two factors that control when we fall asleep, how long we stay asleep, and even how deeply we sleep. These two factors are called circadian rhythms and sleep homeostasis. They work in conjunction with each other (Deboer, 2018) to time and coordinate sleep with your environment and lifestyle. This process of your body aligning sleep with your environment and lifestyle is called entrainment.

The overall effects of sleeping are very interesting and multifaceted. Every part of your body is affected by sleep and many benefits can be attributed to getting a proper night of rest. Cognitive performance increases after sleep in regards to memory consolidation and experiencing insights (Ellenbogen, 2005; Schapiro, 2017; Wagner, 2004). The rejuvenation of proper sleep and taking breaks as needed can actually help you stay focused at work (Kühnel, 2016). Naps are associated with better physical performance, better ability to pay attention, and lower stress levels (Hsouna, 2019; Mah, 2011). Sleep also makes it easier to lose weight by helping stabilize hormone levels, increasing motivation and maximizing athletic performance (Cappuccio, 2008; Di Milla, 2013; Markwald, 2013; Taheri, 2004). You are less likely to get sick from the common cold and you recover faster from it if you are getting a higher quality or longer duration of sleep. (Cohen, 2009).

The benefits of sleep have on your cognitive performance extend to your relationships. Several studies have shown your ability to recognize others’ emotional states and empathize with them increases with better sleep quality (Guadagni, 2014; Schwarz, 2013; Van der Helm, 2010). Empathy is vital to communicating, forming connections, and parenting (Decety, 2016). Self-control and forgiveness are other vital components to maintaining good relationships affected by sleep. In a study on marital relationships, sleep increased the husbands’ ability to overlook negative details of the relationship. The wives did not share this increased ability to overlook negative details of the relationship but still reported being more satisfied in their overall relationship (Maranges, 2017).

How does IBD Disrupt Sleep?

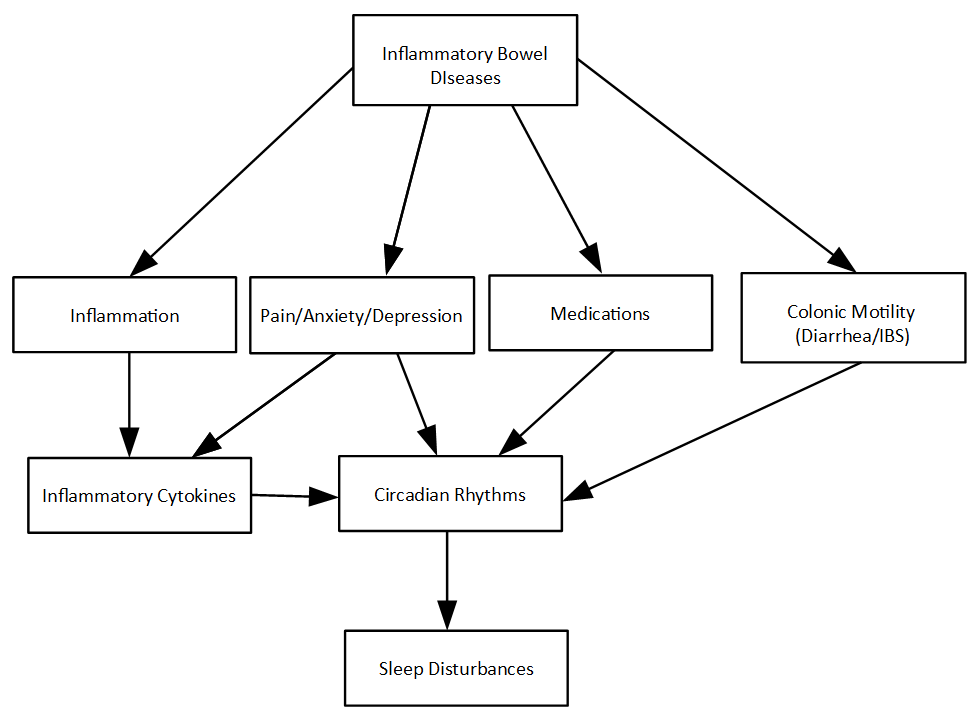

Although we are still learning how sleep influences IBD, the connection has been noticed by many researchers (Canakis, 2020; Ranjbaran, 2006; Risa, 2016; Swanson, 2014). IBD can disrupt sleep through a multitude of mechanisms and there might still be more undiscovered. These mechanisms are part of the immune, endocrine, skeletal-muscular, and gastrointestinal systems in your body. As you can guess from the number of systems connecting sleep and IBD, having a flare can absolutely wreak havoc on your ability to rest.

- Interleukin-1 Beta (IL-1β or IL1B) – This is a pro-inflammatory protein (cytokine) that tells certain white blood cells and receptors that you have been exposed to toxic bacteria. It is released in significant amounts during a flare due to the intestinal lining being inflamed and unable to properly protect you from the bacteria in your gut. IL-1β was the first cytokine found to regulate sleep; it typically causes your brain to experience sleep deprivation. This is good for inspiring sleep and allowing you to rest while sick but it also interferes with your body’s circadian rhythm, sleep homeostasis, and internal temperature. Having a fever, feeling chilled or malaise, and having an out of balance sleep schedule from feeling exhaustion will pose challenges to your ability to get good sleep. Despite increasing the amount of sleep you get, IL-1β will overall cause your quality of sleep to decrease. At extremely high doses it will even directly inhibit your ability to sleep in both nREM and REM stages (Zielinski, 2011). This is contrasted to the increase in nREM sleep seen with smaller amounts of IL-1β.

- Interleukin-6 (IL-6) – IBD also makes Interleukin-6 levels increase during a flare. IL-6 is somewhat similar to IL-1β because it is also a sleep-promoting, pro-inflammatory cytokine. If you are flaring, the increased IL-6 makes you feel very tired. Just like IL-1β, the increased IL-6 induced exhaustion disrupts your circadian rhythms and sleep homeostasis (Späth-Schwalbe, 1998). As your body adjusts its sleep cycles to the disrupted rhythms and homeostasis your quality of sleep suffers. It is also hypothesized that your brain needs levels of IL-6 to drop during sleep to actually feel rested. (Vgontzas, 1996). Ideally, your levels raise appropriately throughout the day to make you tired. Then the levels should drop as you begin to sleep so your nREM and REM stages can function as they would normally.

- Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNFa) – This is perhaps the most well-known inflammatory cytokine amongst the IBD community. Some of the most frequently used treatments for IBD are TNFa blockers; this includes infliximab, adalimumab, and certolizumab. The TNFa blockers have shown a lot of promise in correcting sleep issues caused by inflammatory diseases (Rockstrom, 2018). TNFa will cause your core body temperature to rise, make you feel fatigued, and release more IL-1β and IL-6. This can disrupt your body’s ability to properly cycle through sleep. This is even more true if a cytokine storm develops from TNFa releasing a lot of IL-1β and IL-6.

- Bacterial Endotoxins – Some species of bacteria create toxic metabolites that build up inside the cell and get released upon its death. These endotoxins trigger an inflammatory response inside your body. This is one of the most important triggers of IBD flares. Certain bacteria can help or hurt IBD outcomes depending on whether they generate endotoxins or not. Ideally, we want non-endotoxin-producing bacteria, like those found in yogurt, to overpower and outcompete the endotoxin-producing species in your microbiome. When endotoxins are absorbed through the inflamed intestinal walls they cause TNFa, IL-1β, and IL-6 to be released (Reinecker, 2008). As mentioned above, these pro-inflammatory cytokines will disrupt your body’s ability to regulate its circadian rhythms, sleep homeostasis, and core temperature.

- Pain and Anxiety – Pain and anxiety are unfortunately very common when dealing with IBD. When you experience pain or anxiety your body’s sympathetic nervous system is activated. This system is responsible for the fight-or-flight response when you are faced with a dangerous or stressful situation. This response is known as arousal (hyperarousal when it is more severe) and it causes a variety of symptoms including mental alertness, inflammation, and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). The sympathetic nervous system also inhibits your parasympathetic nervous system which is responsible for relaxation, rest, and digestion. Together all of these effects can very badly impair your ability to sleep at night (Khanijow, 2015; Khassawneh, 2018; Orr, 2002).

- Colonic Motility – While sleeping your colon relaxes during nREM sleep stages, and it becomes slightly stimulated in REM sleep (Furukawa, 1994). The deeper asleep you are during nREM sleep the more relaxed your colon becomes, this allows it to rest and repair. Pain and anxiety from IBD and life stressors can cause you to spend more time in REM sleep due to sympathetic nervous system stimulation. This might limit the ability of your colon to rest during sleep due to overstimulation from spending more time in REM sleep than the resting nREM stages (Khanijow, 2015). Aside from the stimulation from pain and anxiety, the inflammation from IBD can also cause diarrhea. If the diarrhea is severe enough your colon will be unable to contain it, forcing the colon to be more active while sleeping. In several different studies, diarrhea was associated with disrupted sleep patterns (Akechi, 2006; Eswaran, 2016; Watson, 2002).

- Dietary Issues – Having IBD comes with a variety of dietary issues that can affect your sleep. Simply eating at different times or different foods due to IBD can change your sleep patterns (Frank, 2017; Peuhkuri, 2012; St-Onge, 2016). Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) has been found to be associated with sleep issues in IBD, and it has even been suggested as it’s own separate sleep disorder (Ali, 2013; Sofia, 2017). IBD also puts you at a greater risk for a variety of micronutrient deficiencies. Lack of phosphates, vitamin B1 and B9, selenium, zinc, magnesium, and iron have all been associated with a reduction in sleep. Low dietary levels of vitamin C, vitamin D, calcium, and selenium are connected to lower sleep quality and difficulty falling asleep (Frank, 2017; Grandner, 2013).

- Depression – The challenges caused by having IBD can sometimes make you feel depressed, this can especially be true in the long-run. There is some debate over the details of the interaction between IBD and psychological connections due to a lack of high-quality evidence. However, it is somewhat obvious that there is some type of connection between IBD, anxiety, and depression (Mikocka-Walus, 2006). Depression is also the most common psychiatric disorder associated with insomnia (Tsuno, 205). The connection between depression, inflammation, and sleep is debated due to a lack of studies. However, a more recent study of depression was associated with significantly raised levels of IL-6 (Wang, M., 2019). The dysregulation of IL-6 has been associated with sleep abnormalities and could be one possible explanation for the connection between IBD, depression, and sleep issues.

- Medications – IBD treatments can also cause disruptions to your circadian rhythms and sleep homeostasis. Glucocorticoids are notorious for this and a listed side effect for prednisone is trouble sleeping (www.drugs.com, citation #121). A study on rats showed repeated glucocorticoid exposure to impaired sleep after only 7 days of treatment. The glucocorticoid receptors in the locus coeruleus of the brain were desensitized, which activates norepinephrine (noradrenalin) circuits in the brain, which suppress GABAergic activity (Wang, Z., 2015). All of this complicated jargon simply means glucocorticoids can cause nervousness, alertness, and difficulty relaxing; the opposite of sleepiness. Glucocorticoids also affect melatonin, IL-1β, IL-6, and TNFa levels which have a direct impact on your sleep (Brattsand, 1996; Kinnucan, 2013).

What are the Effects of Sleep Disruption?

Even people without IBD are susceptible to sleep issues and the problems that arise from them. Sleep issues influence your entire body in ways that can significantly lower your quality of life. We know this because the importance of sleep was mostly discovered through studies on sleep disruptions and deprivation. These studies have connected sleep deprivation to problems with brain functioning, emotions, physical health, work/school performance, and even your safety (Fobian, 2020; Khassawneh, 2018; Parker, 2017; Salvo, 2020; Touitou, 2017). Not getting enough sleep can make it difficult to focus, react quickly, memorize, and learn new things, and complete physical activities. You are also at a higher risk of developing heart issues, obesity, and mental illness by having subpar sleep quality. The importance of getting adequate sleep can not be stressed enough as it seems to be positively associated with all causes of premature deaths (Irwin,2016; Shen, 2016).

Sleep deprivation also causes significant problems with your immune system. If you become sleep deprived your body experiences higher levels of systemic inflammation (Fernandez-Mendoza, 2017; Irwin, 2016; Prather, 2015). If you are a woman this is even more true as sex differences in the central nervous system, gonadal hormones, and body fat lead you to be more susceptible (Prather, 2013). Everyone (including men) becomes more susceptible to infections like the cold and flu viruses and it becomes more difficult to overcome them (Cohen, 2009; Everson, 2000). Overall, sleep deprivation will weaken your immune system and cause more inflammation.

The Feedback Loop Between IBD and Sleep

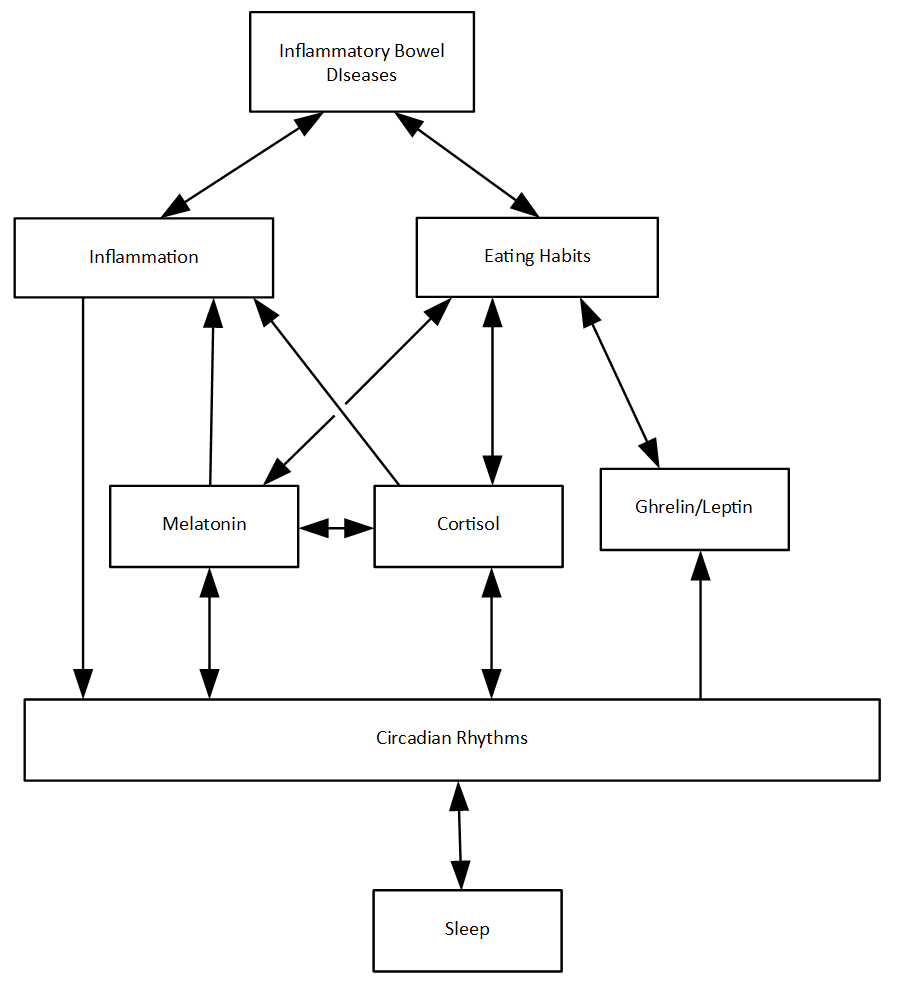

All of this causes a very serious problem for you if you have IBD. The IBD will disrupt your sleep by causing inflammation and other symptoms. The sleep issues will then disrupt your circadian rhythms and immune system, leading to more inflammation that makes the IBD worse (Codoñer-Franch, 2018; Föh, 2019; Liu, 2017; Mukherji, 2013; Thaiss, 2014). It is a vicious cycle of IBD, sleep, and inflammation. This bi-directionality and interconnectivity allows IBD flares and sleep issues to sustain each other if not properly addressed and corrected.

To complicate things even more, the endocrine system is extremely involved in organizing the responses between circadian rhythms and your body’s response to them. This is because circadian rhythms are intertwined with the production of several vital hormones inside your body (Kalsbeek, 2001; Qian, 2018; Reppert, 1981). The hormones are called cortisol, melatonin, ghrelin, and leptin. Cortisol is a glucocorticoid steroid that is extremely similar to prednisone and as such, it is very immunosuppressive. Melatonin is commonly taken as a supplement for sleep, it is immunomodulatory, and it is involved in sleep homeostasis. Ghrelin and leptin are involved in hunger and satiety, which are important to sleep and IBD because of their effects on eating habits.

How Are Hormones Connected to Sleep and IBD?

Hormonal signals and fluctuations are an integral part of the bidirectional relationship between IBD and sleep. This is because hormones act as messengers inside your body to orchestrate all the different functions of the different systems of your body. This is how your brain and certain glands tell other parts of your body that it is time to eat, sleep, wake, stress, etc.

We will focus on the four hormones that appear most directly involved in the influence that IBD and sleep have on each other. Other hormones such as norepinephrine, prolactin, vasopressin, estrogen, testosterone, insulin, etc. have an influence over IBD and sleep as well, but they are a little more indirect and therefore not quite as significant.

Cortisol – This glucocorticoid is found inside your body and used as a medication. However, we call it hydrocortisone when it is used as a medicine for things such as hives, itchiness, and bug bites. Regardless of the name used for it, cortisol is very similar to prednisone (a drug widely used for treating IBD) and has many of the same characteristics. These hormones are extremely immunosuppressive and can stop the inflammation caused by IBD. However, there are difficulties using glucocorticoids like cortisol or prednisone for inflammation due to side effects and resistance to the beneficial effects (Liberman, 2018). Nonetheless, they can be useful for stopping severe IBD flares before finding a more preferable option.

Aside from stopping inflammation cortisol inhibits the sleep-promoting effects of the proinflammatory cytokines like IL-1β and the hormone melatonin. By inhibiting these sleep-promoting substances in your body cortisol causes you to feel more awake. Some of the mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid receptors in your brain are also directly involved in controlling sleep (Born, 1991; Wang, Z., 2015). Cortisol naturally peaks during the morning time and gradually lowers towards night, with several different factors also affecting its levels.

Light has a very significant effect on cortisol levels that can be manipulated to change your circadian rhythm of cortisol. For example, very northern countries such as Sweden have very long days during summer. The sunlight makes it extremely difficult to fall asleep, so it is common to see heavy drapes on most houses there. By lowering the light levels in the house cortisol levels begin to drop, and everyone starts to feel sleepy. Although light is influential, stress is perhaps the most powerful influence over cortisol levels. Cortisol is commonly referred to as the “stress hormone.” The connection between stress and IBD is heavily mediated through cortisol levels and glucocorticoid receptors (Brzozowsk, 2016). IBD patients might even be more physiologically sensitive to the effects of stress (Farhadi, 2003). Aside from circadian rhythm disruptions, the dietary changes caused by IBD can also influence levels of cortisol in your body, which could be one explanation for the increased sensitivity to stress in some IBD patients (Stachowicz, 2016). You can think of cortisol as a mediator between wakefulness, sleep, diet, stress, light, and inflammation; it is an extremely important hormone.

Melatonin – Melatonin is still not well understood, but we do know it is involved in modulating inflammation and sleep. In a manner opposite to cortisol, melatonin starts out low in the morning and slowly increases as the day progresses. Like cortisol, it is entrained to the amount of light hitting your retinas. Unlike cortisol, light is the most influential factor in melatonin levels as compared to stress for cortisol. When the levels of melatonin increase in your body from being exposed to light you begin to feel more sleepy.

In regards to inflammation, it changes how the mucosal membranes inside your body react to bacteria. This means melatonin could possibly be used as an adjunct therapy for some IBD sufferers who also have melatonin imbalances (Kim, 2020). Melatonin levels and the receptors for it might be altered in a subgroup of IBD sufferers (Burgess, 2010; Chen, 2011; Swanson, 2014; Wang, B., 2019). However, the involvement of melatonin is not consistent in all people with IBD, in fact, most people with IBD do not have melatonin issues. It might be possible that only people with both IBD and melatonin imbalances benefit from the anti-inflammatory properties of melatonin supplements. If we can figure out why only certain people respond to melatonin it will most likely start to be utilized in IBD therapy. Currently, several melatonin receptor activators have already been developed for insomnia and more research is being done to improve the efficacy of them (Srinivasan, 2009).

Ghrelin – This hormone is most known as the “hunger” hormone because its main purpose is to stimulate eating. It is mostly involved in metabolism, memory, reinforcing rewarding behaviors, and sleep. Ghrelin naturally follows a circadian rhythm that is independent of lifestyle factors (Qian, 2016), but it can also be manipulated through things like temperature, exercise, and dietary changes. As you might guess, levels of ghrelin are the highest right before eating and lowest after eating. The amount of ghrelin in your body partially explains why you do not feel as hungry in the morning or immediately after eating a large meal. A study on the levels of different cytokines produced by body fat tissues found elevated levels of ghrelin in IBD patients compared to healthy controls. However, the significance of this discovery is not yet known (Karmiris, 2006; Sobolewska-Włodarczyk, 2020).

Ghrelin is generally sleep-promoting and has an influence over the levels of other hormones (cortisol, prolactin, ACTH, growth hormone, etc.) while you are asleep (Weikel, 2003). Despite evidence that ghrelin promotes sleep, there have been some contradicting studies done that show the opposite. Some suggestions for this paradoxical effect are that the discomfort from extreme hunger caused by high levels of ghrelin interrupts sleep, or there are differences between rats, mice, and humans (Steiger, 2007). More studies into the interaction between sleep and ghrelin are certainly warranted, especially with the unknown relationship between IBD and raised levels. Ghrelin and its receptors might lead to novel therapies for metabolic disorders, obesity, sleep problems, and gastrointestinal diseases.

Leptin – This hormone does essentially the opposite of ghrelin and makes you feel satiated. It follows a circadian rhythm and fluctuates depending on when you are most active and eating. Your body’s levels of leptin can be disrupted by sleep problems, and if the levels stay disrupted for too long your body can become resistant to leptin (Kettner, 2015). If this happens your body stops responding as well to the leptin available. This has been associated with disrupted eating habits, obesity, other metabolic disorders (Arble, 2011; Lalazar, 2015). Leptin is seen in lower amounts in patients with active IBD, but the significance of this is also still not understood (Karmiris, 2006; Sobolewska-Włodarczyk, 2020). The connection between IBD, Sleep, and leptin could be partly explained through it’s interactions with the immune system. Leptin has shown to be influential in intestinal inflammation through several mechanisms (Weidinger, 2018). Although ghrelin and leptin will most likely not be used as treatments themselves, understanding their involvement in the relationship between sleep and IBD will create new treatment options.

What is Chronotherapy?

Time is a common variable between all the different hormones entrained to a circadian rhythm. Due to the influence of hormones on multiple biological processes and cells in your body, time is essential to everything. The timing of when you take medications, eat meals, exercise, sleep, or see light can all have an influence on your health. Chronotherapy is the utilization of timing different lifestyle factors in a therapeutic manner. Chronotherapy was originally developed for conditions such as psychiatric disorders, cancers, and sleep problems, but it slowly becoming more relevant in all domains of medicine. It can be used to improve drug effectiveness, correct imbalanced circadian rhythms, and sleep problems, and improve general health by reducing the negative effects of circadian disruptions.

Chronotherapy has previously been studied in regards to glucocorticoid use in rheumatoid arthritis. There are benefits to using split doses and extended-release formulations in rheumatoid arthritis (Naafs, 2018). Why chronotherapy has not been studied with the widespread use of glucocorticoids in IBD is absolutely confounding. Improvements to the timing of when glucocorticoids are dosed can lower systemic side effects, prevent treatment resistance, and improve the outcomes in inflammatory diseases (Rohan, 2012).

Unfortunately, without specific guidelines and more research, it is difficult to impossible to make suggestions at this time regarding chronotherapy for IBD. However, there are some generalized tips that can possibly lead to an improvement in your sleep and IBD. Some of these tips pertain to the timing of certain lifestyle habits and could be considered very basic chronotherapies.

What Lifestyle Changes can Help?

“Life habits such as sleep, physical exercise, social interaction, and feeding times are determinants for stability and integrity of circadian rhythms.” (Codoñer-Franch, 2018). You can use different lifestyle changes to optimize your sleep and IBD whether you are in a flare or not. Most of these changes can take several days to weeks to make a significant difference so it’s best to make a habit of them. Try introducing one change at a time for several weeks before trying something else so you can determine what helps the most, doesn’t help as much, or makes things worse. Luckily sleep and IBD are bi-directionally related to each other, so anything that helps with one should help with the other!

Exercising – Exercise is beneficial in lowering inflammation and preventing some of the complications of IBD like muscle and bone density loss (Bilski, 2014). Although the mechanisms are not understood, it has been shown to be beneficial in both adults and juveniles (Legeret, 2019). Light to moderate exercise did not seem to make symptoms of IBD worse, but patients frequently reported having to stop due to IBD symptoms like joint pain (Chan, 2013). Several types of low to moderate-intensity exercise have been studied and found to be beneficial and well-tolerated by people with IBD including walking, light running, yoga, dancing, and exergaming (Gupta, 2006; Legeret, 2019; Loudon, 1999; Nathan, 2013; Ng, 2007).

There is concern about overexertion causing exercise‐induced gastrointestinal syndrome. This occurs even in healthy people (regardless of fitness level) so it is advisable to pace yourself and set limits in your exercise routine (Costa, 2017). If you are currently having sleep issues you should avoid strenuous exercise and only engage in light to moderate exercise. This is due to a possible increased risk of exercise-induced diseases (such as sudden cardiac death) and physical injuries when sleep deprived (Chennaoui, 2014). Crohn’s patients might also want to consider taking a multivitamin containing vitamin C and E (both are antioxidants) and zinc before exercising to limit oxidative damage and prevent zinc deficiencies. There is very weak evidence that acute severe exercise could make oxidative damage from neutrophils worse in Crohn’s disease as well as worsening the chance of developing a zinc deficiency (D’Incà, 1999; Alzoghaibi, 2013). However, chronic moderate exercise was found to inhibit neutrophils and this effect lasted after exercise was stopped (Syu, 2011). Sticking to the exercise routine you planned will start to show benefits even with the slight increase in inflammation from when you first start out.

There is limited to no data on how much exercise, what type, and when doing so benefit sleep. However, we do know the relationship between exercise and sleep is also bidirectional like sleep and IBD (Kline, 2014). Many people have wrongfully assumed that exercising later in the day disrupts their circadian rhythm, but most evidence shows it is beneficial. Extreme physical stress from overexertion less than an hour before bedtime can possibly negatively affect sleep. This is due to the intensity of the workout and the subsequent stress, not when the exercise was done (Stutz, 2019). Moderate intensity exercising (in addition to being safer) is also more effective at improving sleep as compared to strenuous exercise (Wang, F., 2019). With all of this in mind, try to follow these guidelines for exercising to improve your sleep and IBD:

Pick a convenient time to dedicate to exercising, this makes it easier to be consistent with your workout routine. Exercise only helps if you stick with it! Make it a habit and you will find it much easier.

Do not overexert yourself or exercise too much, this will only increase inflammation and could possibly lead to injuries. If you are uncertain about your limits, start with light stretching and walking. Talk to your doctor or a physical therapist if you have any heart condition or a condition that limits your movement and ability to exercise normally.

Most of your routine should consist of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise rather than resistance and strength training. Resistance and strength training is beneficial but slightly less so than aerobic training, they can also cause injury much easier. Use more caution when doing resistance and strength training and consider consulting a professional such as a physical therapist or professional trainer to help guide you.

Adjusting Glucocorticoid Use – Using glucocorticoids can disrupt your circadian rhythm but you might need them to keep your IBD in control. Luckily there are several different adjustments that can be useful in maximizing the effectiveness of glucocorticoids while also minimizing the side effects. Talking to your doctor about these changes is necessary since glucocorticoids like prednisone, prednisolone, or budesonide require a prescription. Improper tapering or dosing of these medications can also have serious health consequences so medical supervision is vital to maintain your safety.

Taking glucocorticoids in the late morning or early afternoon might help improve the effectiveness of the medication while also causing fewer side effects from the suppression of your natural cortisol. Levels of cortisol peak in the morning and taking glucocorticoids early in the morning (12:00 am to 8:00 am) was associated with adrenal suppression, side effects, and fewer benefits in studies of rheumatoid arthritis and asthma (Cutolo, 2016; Krakowiak, 2018; Naafs, 2018). Some patients also take a split dose where 2/3 of the dose is taken in the morning (9:00 am to 12:00 pm) and 1/3 is taken in the afternoon (12:00 pm to 4:00 pm) to try and attempt a more natural wave similar to the ebb and flow of cortisol. Alternate day dosing (skipping a day between doses) has also helped some patients keep their symptoms in check while minimizing how much medication is needed and the side effects associated with it (Nicolaides, 2018). Despite what studies on rheumatoid arthritis and asthma have shown us, you should tailor a specific time schedule for dosing with your doctor’s help. Studies have shown differences in circadian rhythm genes in different medical conditions, even between different forms of IBD (Codoñer-Franch, 2018). The biology of everyone’s body is slightly different, so what works best for you might be different than what works for others even if they have the same condition as you.

If timing, dose splitting, and alternating days do not help improve your sleep quality and IBD, consider alternative formulations or medications. There are many different glucocorticoids and formulations of the same types of glucocorticoids. For example, some people do better with budesonide compared to prednisone (Brattsand, 1990; Bonovas, 2017). Delayed-release formulations are somewhat less studied and used, but might also be an option for you. Delayed-release prednisone is not common due to the cost of the medication, but it is available if you are wealthy or have universal healthcare where you live. It has been shown to benefit rheumatoid arthritis patients and may someday be the preferable treatment option once generics are available (Cutolo, 2016). Unfortunately, your doctor is most likely unaware of chronotherapy and the importance of timing doses with certain medications. Studies have found more than 90% of prescriptions for rheumatoid arthritis is for early-morning dosing of glucocorticoids (Naafs, 2018). Considering there is less research on the circadian rhythms of IBD a similar lack of awareness is expected as well amongst doctors treating IBD patients.

Other medications might be more viable alternatives to long-term glucocorticoid use if you do not respond well to them. These include things such as immunomodulators, biologics, and complementary and alternative medicines (Ford, 2011; Graham, 2007; Mijan, 2018; Sunil, 2009). If you are using a non-glucocorticoid drug or plan to switch to one, consider their timing as well. Studies on the applicability of chronotherapy with glucocorticoids also suggest chronotherapy could be applied to other drugs that are meant to treat symptoms entrained to a circadian rhythm (Cutolo, 2016).

Scheduling Daily Tasks– Keeping a consistent schedule of when you eat meals and do routine tasks will help keep your circadian rhythms stable. Multiple studies have shown a connection between social rhythms (when you do tasks throughout the day), circadian rhythms, and sleep quality (Moss Atlin, 2014). This also applies to children and the elderly even though they have different sleep patterns (Mindell, 2018; Zisberg, 2010). The regularity of daily activities and meals was significantly dysregulated in connection with sleep issues. This was most noticeable for lunch and evening eating habits for people suffering from insomnia.

Waking up every day at the same time, eating breakfast, lunch, and dinner at the same times, as well as scheduling daily activities for the same times will make a drastic change in your stress levels and sleep. Maintaining your awareness of what time it currently is and what stage of your day you should be in for that time is essential to keeping your circadian clocks entrained. The best way to do this is to make a habit of checking a clock periodically throughout the day, if you are the forgetful type, then setting alarms might help. By tracking the day’s progression you can better align your social rhythms to the natural 24hr day even when your circadian rhythms are misaligned. For example, you might not feel tired later in the evening after flaring for several weeks and your circadian rhythm subsequently becoming disrupted. Despite this disruption, you can still set an alarm at 10:00pm to remind you that you should start your bedtime routine. As you start your bedtime routine it creates stimuli your body associates with sleep, this stimulates certain sleep-promoting substances like melatonin and your circadian rhythm adjusts to the current situation. This will not necessarily eliminate all of your sleep issues or IBD flare and reset your circadian rhythm, but it will help correct them as part of your collective treatment plan. The logic behind these small changes is that they will eventually add up and make a much more significant change to the outcome of your IBD.

Controlling Light – This is considered the most powerful way to entrain your body’s circadian clocks and rhythms to the natural 24hr cycle. If you are completely blind, entraining your circadian rhythms to the 24-hour cycle might even be impossible (Klein, 1993). When light hits your eyes it sends signals to your brain that it is time to be awake. This is affected by how bright the light is, what direction it is coming from, how long you have been exposed to the light, and what color the light is. All of these factors help your brain distinguish whether it is morning, afternoon, evening, or night. Unfortunately, these factors can also be disrupted by electronics, seasonal changes, weather patterns, or travel (Chang, 2015; Föh, 2019; Takahashi, 2002; Zheng, 2019). The good news is you can utilize light as a form of therapy for maximizing the quality of your sleep. Despite only mild to moderate benefits, the effects of light therapy have been found to be consistently beneficial (Van Maanen, 2015). Here are some suggestions for using light to your advantage:

Changing the spectrum of light you are exposed to throughout the day is a great way to simulate the natural change in the ambient light as the sun comes up and goes down. Your brain associates bright light on the blue end of the spectrum with daytime and dimmer light on the red end of the spectrum with the evening. By creating a more natural color of light throughout the day your body is better able to prepare itself for waking up and going to sleep. A study done on the effects of artificial light on people living in Antarctica without exposure to sunlight found white and blue light helped suppress melatonin and promote wakefulness. Blue light had a slightly stronger effect than white light but both were considered adequate for entraining circadian rhythms (Francis, 2008). Other studies have confirmed that the spectrum of light we are exposed to has a significant effect on sleep and wakefulness (Geerdink, 2016; Santhi, 2012). By switching your bedroom lighting to soft white or warm white light bulbs in the 2,700 to 4,000 Kelvin range you can create a less stimulating environment. The warm red, yellow, and orange tones of these light bulbs make the room feel more relaxing and cozy. Places where you are more active such as the bathroom, kitchen and workspaces like your office should have either bright white or daylight bulbs in the 4,000 to 6,500 Kelvin range to help you stay awake and alert. Some electronics and newer models of light bulbs are capable of switching between the different color temperatures. If you have one of these devices it is best to use the bright white or daylight setting during the daytime and then switch to the soft white or warm white setting in the evening while relaxing. Sometimes these settings are referred to as “blue-blocking” or the “night-light” features, but they all change the light on your device to a warmer, softer color to help prevent blue light tones from keeping you awake in the evening and night.

The timing of your exposure to light is another variable you have some control over. When you are exposed to light can either help or hurt the stability of your circadian rhythms. Using thick curtains or blinds to block the light from outside as well as dimming the lights in your house at a regular time every evening can help you get to sleep (Zerbini, 2018). Alternately, using bright lights inside or letting in sunlight during the early morning and afternoon can also help you wake up and not feel drowsy during the middle of the day (Dawson, 1991; Smolders, 2012). Many different light therapies that use timed light-exposure have been suggested and tested with limited success (Geerdink, 2016; Gooley, 2008). The main consistency in all of them is the stimulating effects of light exposure and sedating effects of darkness, your body is designed to work best during the brightest hours of the day.

The brightness of the light in your life is equally as important as the color and timing of your exposure to the light. Bright light is best for maintaining alertness and dim light is best for preparing for sleep and relaxation. Light intensity can actually have direct effects on how your body processes food by changing how your autonomic nervous system and hormones function throughout the day. Eating in dim lighting during the day, or bright light in the evening and night can cause deficiencies and difficulty properly digesting carbohydrates (Hirota, 2003; Lee, 2001). It is best to mimic the natural increase and decrease in brightness throughout the day. This can be accomplished by using dimmer switches and light bulbs, turning on more or fewer lights, and opening and closing curtains or blinds. Setting an alarm can help you remember when it is time to start brightening or darkening your day if you find it difficult to remember.

Utilizing Therapy – Another way to improve your sleep is by addressing some of the anxiety, depression, and stresses caused by IBD with psychotherapy. Some studies have shown improvements in quality of life in IBD patients who use various forms of psychotherapies. Although these therapies did not improve the underlying inflammation they did help with stress levels and sleep (Torres, 2019). These included therapies such as meditation, mindfulness, relaxation, yoga, hypnotherapy, and cognitive behavioral therapy. There have also been similar responses to psychotherapies in regards to sleep quality in conditions other than IBD (Garland, 2014; Martínez, 1995; Vitiello, 2009). With so many different options available psychotherapy can be very versatile. Yoga is particularly interesting because many modern forms of it also incorporate exercise, which is also beneficial for sleep and IBD.

Avoiding Negative Influences – Sometimes the best way to correct sleep issues is eliminating different stimuli and habits that negatively influence your sleep quality. Some of the most common culprits causing sleep issues are:

Alcohol and drug abuse – Both alcohol and drug abuse are connected to poor sleep quality. Every drug affects sleep differently and to different magnitudes, but a majority of addictions seem to cause some type of sleep disturbance (Devenney, 2019; Gordon, 2019). Even light daily drinking to cope with anxiety or sleep problems seems to be connected to sleep problems (Chueh, 2019). Try to avoid abusing alcohol or drugs and if you are currently experiencing addiction seek treatment.

High temperatures and relative humidity – High temperatures and humidity in your bedroom can significantly interfere with your sleep (Okamoto-Mizuno, 1999; Tsuzuki, 2004). If your bedroom is consistently over 78°F (25°C) or 60% relative humidity you might want to consider buying either an air conditioner or dehumidifier. Keeping your room at cooler temperatures and relative humidity around 40 to 60% will create an environment best suited for good sleep.

Noise and light pollution – Both are unfortunately very common due to electronics in bedrooms and artificial light from streetlights coming through windows. If you live in an urban environment or in a shared household noise pollution might also be a frequent problem. The sleep-disrupting effects of light and noise have been studied very well, and are a known problem for hospital patients (Kamdar, 2017; Simons, 2019; Touitou, 2017). To help prevent light pollution make sure all lights are shut-off. If they can not be shut-off then simply covering the light with a piece of thick tape is a popular trick. If there is a window in your room that lets in artificial light from security or streetlights you should consider installing blinds or curtains that do a very good job of preventing the light from illuminating your room. Noise pollution can be reduced by wearing earplugs, insulating your room better, and using white-noise or music. Studies have found the overall noise level is not as important as sudden increases in volume when disrupting sleep (Stanchina, 2005). Listening to white-noise or music can increase your tolerance to jarring noises, by decreasing the difference in volume between the baseline volume of noise and the bursts of louder noises. This process, known as auditory masking, essentially makes the bursts of louder noises less noticeable to your brain while you sleep. It is best to use structured noise like music or recordings of nature and speech because unstructured noise can worsen hearing damage and tinnitus (Attarha, 2018).

Jet lag and social jet lag – Both are frequently caused by demanding work requirements, deadlines, and schedules. Jet lag is the circadian disruption caused by traveling, it is the worst when traveling east and by airplane. Many people who are required to travel for work have significant sleep and alertness issues due to jet lag (Bourgeois-Bougrine, 2003). When staying up late due to an imbalance between your life and sleep schedule causes you to become sleep deprived it is known as social jet lag. It is the disruption caused by late-night work or social activities that you prioritize over sleep (Wittmann, 2006). You will normally notice it when the weekend or a holiday gives you a chance to catch up on sleep. If you find yourself sleeping extra hours on the weekends and holidays and staying up late because of how busy your life is then you are most likely experiencing social jet lag. Scheduling extra time to sleep and napping when possible are some of the best countermeasures to jet lag and social jet lag. Many experienced travelers will suggest sacrificing an entire day after a long-distance flight to rest and reset your circadian rhythm. Pilots are known to utilize naps to maintain alertness and prevent human errors when operating aircraft and experiencing severe jet lag from multiple flights (Samel, 2009).

What Supplements and Foods can Help?

If lifestyle adjustments are not helping you get better sleep there are several different supplements that have shown some promise. Not all of these supplements work for everyone and there is limited evidence for their use in sleep disorders, so it might be necessary to try several different ones to find something that works for you individually. You should also check with your doctor before trying any new supplements to make sure they will not interact with any medications you take and are not contradicted for any medical conditions you might have. For example, caffeine is not suggested for people with specific heart conditions and high-tryptophan foods are to be avoided when taking medications like monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOI’s). All precautions aside, here are some of the best-known supplements for helping get the best sleep possible:

Tryptophan-Rich Foods – Certain foods contain an amino acid known as tryptophan. Your body uses tryptophan to produce serotonin inside your intestines. How much serotonin your body produces and what your body does with the produced serotonin have a significant effect on your sleep. There have been many studies done on the sleep-promoting effect of dietary tryptophan (Idzikowski, 1986; Monti, 2011; Van Dalfsen, 2019). Some people even joke about feeling sleepy after consuming tryptophan-rich foods. However, there have been several setbacks to the use of tryptophan supplements. First, there was an outbreak of eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome (EMS) in the late 1980s that was found to be caused by tryptophan supplements. The outbreak stopped with the widespread use of tryptophan supplements being discontinued. However, several other cases have been reported from different sources as illegal sales and use have continued (Allen, 2011). Secondly, tryptophan can be transported and used differently by your body depending on your ethnicity, sex, genetics, medications, and medical conditions (Ensrud, 2006; Gressier, 2015; Noskova, 2008; Shajib, 2014; Van Dalfsen, 2019). For example, early studies have shown variations in the gene responsible for serotonin transporters in IBD patients, with differences between microscopic colitis, ulcerative colitis, and Crohn’s disease (Goldner, 2015; Sikander, 2014; Shajib, 2018). This means tryptophan-rich foods will help certain individuals more than others and currently, there is no test to determine who. Between our inability to determine how tryptophan supplements (but not natural tryptophan found in food) cause EMS and how individuals react differently research has mostly stopped.

Despite the safety issues with synthetic tryptophan supplements and our inability to determine how effective tryptophan-rich foods will be for your sleep quality, you can still try some of these foods at home. Always consider if these foods will conflict with your IBD diet-restrictions as some of the tryptophan-rich foods are possible trigger foods for some individuals. The goal is to find tryptophan-rich foods that you can tolerate eating and to eat them for several weeks to help optimize your sleep quality. If you have been told to avoid tryptophan-rich foods due to using a MAOI or SSRI you will want to talk to your doctor before including more of these foods in your diet.

- Milk and Cheese

- Turkey and Chicken

- Eggs

- Tofu and Soy

- Pumpkin, Chia, and Flax Seeds

- Peanuts and Peanut Butter

- Oats and Legumes

- Fish and Shellfish

- Beef, Pork, and Lamb

Melatonin – Melatonin is one of the most commonly used supplements for sleep issues. It has shown the potential to help some individuals fall asleep at night. It has been suggested as a possible treatment for insomnia, jet lag, and other circadian rhythm disruptions (Beaumont, 2004; Palm, 2008; Zisapel, 1999). There are limitations to its effectiveness and like tryptophan, we are not sure how to predict who will benefit most from its use (Kamei, 2001; Magee, 2020). Melatonin supplements should also be taken with caution as there have been reports of them both helping and hurting IBD patients (Sánchez-Barceló, 2010). This is most likely due to the important role melatonin plays in immune regulation, mucosal membrane protection, and gut motility. Typically melatonin suppresses cortisol and increases pro-inflammatory cytokines, this could be very undesirable for someone with IBD if it occurred in an inappropriate context. However, if you are experiencing severe circadian disruption and insomnia from your IBD flare, or have difficulties with gut motility and mucus then melatonin might be more beneficial than harmful. Essentially, if the proinflammatory effects of melatonin are less powerful than the benefit it has on your sleep, mucosal membranes, and gut motility. With this in mind, if you want to try melatonin supplements the suggested dose is between 1mg to 5mg a day. It is best to take it in the evening or night shortly before bed to simulate the natural increase that occurs in your body as you are exposed to less light in the evening. Taking more melatonin than suggested will not make it work better and could have adverse effects due to it being an important hormone in your body. You should discontinue using it if your IBD gets worse, reported cases of IBD worsening with melatonin got better upon discontinuing supplementation (Sánchez-Barceló, 2010). In some animal studies melatonin helped with colitis initially but then worsened it with chronic use (Marquez, 2005). If you are starting a regimen of melatonin be aware that the effects it has on your IBD might change over the course of several weeks and require adjustments or discontinuation.

Caffeine – Caffeine has been used with success in combating fatigue and jet-lag but has been unable to entrain circadian rhythms to help with sleep problems (St-Hilaire, 2015; Wright, 2003). There are some studies that show the benefits of caffeine on wakefulness come at the cost of lower sleep quality (Beaumont, 2004; Landolt, 1994). Despite its usefulness for staying alert, it is not used in IBD for a number of reasons including its effects on stress hormones and gut motility, ability to block thiamine and magnesium from being absorbed, and the ability to stimulate stomach acid and gut motility (Dhir, 2019; Rafetto, 2004). Stress and the stress hormones cause blood flow to be directed away from the gastrointestinal tract, this can cause indigestion. Stress hormones are also very proinflammatory despite coffee and caffeine sometimes having anti-inflammatory effects. This complex interaction between caffeine and the inflammatory response makes caffeine a risky drug to ingest if you have IBD (Clrs, 2017). Some people with IBD may benefit from it, but generally, IBD patients who abstain from caffeine consumption do better (Barthel, 2020; Magee, 2005).

Cannabidiol – Many people report having success using cannabidiol supplements for sleep issues. Several studies in animals and humans have shown the same positive results (Babson, 2017; Chagas, 2013). Unfortunately, drug side effects are very common with cannabidiol (Brown, 2019). Some studies have also found little to no benefit from cannabidiol on sleep in healthy adults with acute use, but suggest it could be different with chronic use or in certain conditions (Linares, 2018). The uncertainty of cannabidiol’s effects on sleep in different people and the frequency of drug interactions has limited its clinical application. If you would like to try using cannabidiol as a sleep aid it is best taken shortly before bed in the evening. The dose depends on the type of CBD-containing product used; always make sure you follow the directions provided.

Essential Oils – There are a variety of essential oils from plants that have been investigated as potential sleep aids. The essential oil most commonly used for improving sleep is lavender (Lillehei, 2014). Lavender has been traditionally used for a variety of medical uses and has shown promise with a few neurological problems as well, including sleep issues (Koulivand, 2013). A variety of consumer products now include lavender oil as an ingredient to help you fall asleep or stay asleep. Women might notice a stronger effect than men and it is more useful for milder cases of insomnia than severe cases (Goel, 2005). A separate compound found in the essential oil of pine trees called pinene has helped some people use less of the sleep medication zolpidem (Salehi, 2019). It has a mild sedative effect similar to lavender and can be found in some of the same plants as lavender (Guzmán-Gutiérrez, 2012). You can find many different essential oils and tools for using them being marketed for “aromatherapy”. They are generally safe if used as directed with the exception of contact dermatitis and allergies. However, you should always use caution with essential oils and storage. Many of them are extremely toxic if ingested and account for a significant amount of pet and small child poisonings (Flaman, 2001; Wismer, 2019).

Will Specific Sleep Therapies Ever Exist for IBD?

There has been a serious lack of coordinated efforts in addressing the lifestyle factors that affect IBD patients. Diet is one of the most important factors and only recently have significant recommendations been made to fix the lack of information available to patients (Rondanelli, 2020). It could take several more years before this information is spread to a majority of the medical providers treating IBD patients and it is fully implemented. Sleep is not as well recognized as an influence on IBD as diet, and therefore can be expected to take slightly longer before specific guidelines and therapies exist on a large-scale. Fortunately, groups like the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation have begun to research possible therapies for sleep issues in the IBD community (Hashash, 2020). More and more studies are confirming the connection between active IBD and sleep disturbances (Conley, 2020; Qazi, 2018; Van Langenberg, 2015). As greater awareness of the bidirectional relationship between sleep and IBD grows more research will be done, and more providers will begin to screen for sleep issues and offer appropriate therapies. Until then supporting groups and individuals who research sleep and IBD, and being your own advocate by explaining your medical needs to your providers are the best option. Active efforts and patience can make a significant difference over a long period of time.

The Takeaway…

Sleep disturbances are becoming a more recognized extra-intestinal manifestation of IBD. During a flare, you should report any sleep issues you are experiencing and work with your medical team to get your IBD under control. Once your IBD is under better control any sleep issues you are experiencing will become much easier to improve. Because of the bidirectional nature of the relationship between sleep and IBD any sleep issues you have can be contributing to your IBD flares. Addressing issues like sleep apnea, seasonal affective disorder, uncomfortable sleeping conditions, and insomnia will lessen the inflammation and fatigue you experience from flaring. It is very important to treat both IBD and any sleep issues at the same time to improve the efficiency of the treatments. There are several lifestyle changes and supplements you can try at home to try to improve your quality of sleep. If you are still having sleep issues despite your best efforts your doctor can try stronger medications, medical devices, behavioral therapies, and other sleep therapies. As more research is completed on the connection between sleep and IBD more IBD-specific therapies will become available for sleep disturbances. In the meantime using the available treatments, living healthy lifestyles, and supporting research efforts are some of the best strategies in moving forward towards a better quality of life while living with IBD.

Judd Harper is an independent contractor, entrepreneur, and proud parent. He studies multiple subjects including medicine, organic chemistry, pharmacology, botany, and mycology. He successfully uses Complementary and Alternative Medicines (CAM’s) for his Crohn’s disease and advocates for health care reform and informed consent. He loves to spend time with his son, garden, listen to music, and learn new languages. He can be contacted at juddtharper@gmail.com with any questions or business solicitations.

References

- Ahmed, O. J., & Cash, S. S. (2013, August 12). Finding synchrony in the desynchronized EEG: The history and interpretation of gamma rhythms. Retrieved July 29, 2020, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3740477/

- Akechi, T., Okuyama, T., Akizuki, N., Shimizu, K., Inagaki, M., Fujimori, M., . . . Uchitomi, Y. (2006, November 06). Associated and predictive factors of sleep disturbance in advanced cancer patients. Retrieved August 08, 2020, from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/pon.1122

- Ali, T., Choe, J., Awab, A., Wagener, T. L., & Orr, W. C. (2013, December 28). Sleep, immunity and inflammation in gastrointestinal disorders. Retrieved August 09, 2020, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3882397/

- Allen, J. A., Peterson, A., Sufit, R., Hinchcliff, M. E., Mahoney, J. M., Wood, T. A., . . . Varga, J. (2011, November). Post-epidemic eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome associated with L-tryptophan. Retrieved September 30, 2020, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3848710/

- Alzoghaibi, M. A. (2013, October 21). Concepts of oxidative stress and antioxidant defense in Crohn’s disease. Retrieved August 22, 2020, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3801366/

- Arble, D., Vitaterna, M., & Turek, F. W. (2011, September 11). Rhythmic Leptin Is Required for Weight Gain from Circadian Desynchronized Feeding in the Mouse. Retrieved August 21, 2020, from https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0025079

- Attarha, M., PhD, Bigelow, J., PhD, & Merzenich, M. M., Ph. (2018, August 30). Unintended Consequences of White Noise Therapyfor Tinnitus—Otolaryngology’s Cobra Effect. Retrieved September 25, 2020, from https://www.hearingassociatesmc.com/images/pdfs/JAMA-Unintended-Consequences-of-White-Noise-Therapy-for-Tinnitus.pdf

- Babson, K. A., Sottile, J., & Morabito, D. (2017, March 27). Cannabis, Cannabinoids, and Sleep: A Review of the Literature. Retrieved November 10, 2020, from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs11920-017-0775-9

- Barthel, C., Wiegand, S., Scharl, S., Scharl, M., Frei, P., Vavricka, S. R., . . . Biedermann, L. (2015, August). Patients’ perceptions on the impact of coffee consumption in inflammatory bowel disease: Friend or foe? – a patient survey. Retrieved November 10, 2020, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281371745_Patients%27_perceptions_on_the_impact_of_coffee_consumption_in_inflammatory_bowel_disease_friend_or_foe_-_a_patient_survey

- Beaumont, M., Batéjat, D., Piérard, C., Van Beers, P., Denis, J. B., Coste, O., . . . Lagarde, D. (2004, January 01). Caffeine or melatonin effects on sleep and sleepiness after rapid eastward transmeridian travel. Retrieved November 03, 2020, from https://journals.physiology.org/doi/full/10.1152/japplphysiol.00940.2002

- Bilski, J., Brzozowski, B., Mazur-Bialy, A., Sliwowski, Z., & Brzozowski, T. (2014, April 30). The role of physical exercise in inflammatory bowel disease. Retrieved August 23, 2020, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4022156/

- Bonovas, S., Nikolopoulos, G., Lytras, T., Fiorino, G., Peyrin‐Biroulet, L., & Danese, S. (2017, December 22). Comparative safety of systemic and low‐bioavailability steroids in inflammatory bowel disease: Systematic review and network meta‐analysis. Retrieved August 27, 2020, from https://bpspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/bcp.13456

- Born, J., DeKloet, E. R., Wenz, H., Kern, W., & Fehm, H. L. (1991, February 01). Gluco- and antimineralocorticoid effects on human sleep: A role of central corticosteroid receptors. Retrieved August 18, 2020, from https://journals.physiology.org/doi/abs/10.1152/ajpendo.1991.260.2.e183

- Bourgeois-Bougrine, S., Carbon, P., Gounelle, C., Mollard, R., & Coblentz, A. (2003, October 01). Perceived Fatigue for Short- and Long-Haul Flights: A Survey of 739 Airline Pilots. Retrieved September 27, 2020, from https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/asma/asem/2003/00000074/00000010/art00010

- Brattsand, R. (1990). Overview of Newer Glucocorticosteroid Preparations for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Retrieved August 27, 2020, from https://www.hindawi.com/journals/cjgh/1990/708916/

- Brattsand, R., & Linden, M. (1996). Cytokine modulation by glucocorticoids: Mechanisms and actions in cellular studies. Retrieved August 14, 2020, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8899106/

- Brown, J. D., & Winterstein, A. G. (2019, July 08). Potential Adverse Drug Events and Drug–Drug Interactions with Medical and Consumer Cannabidiol (CBD) Use. Retrieved November 11, 2020, from https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/8/7/989

- Brzozowski, B., Mazur-Bialy, A., Pajdo, R., Kwiecien, S., Bilski, J., Zwolinska-Wcislo, M., . . . Brzozowski, T. (2016). Mechanisms by which Stress Affects the Experimental and Clinical Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): Role of Brain-Gut Axis. Retrieved August 18, 2020, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5333596/

- Burgess, H. J., Swanson, G. R., & Keshavarzian, A. (2010, June). Endogenous melatonin profiles in asymptomatic inflammatory bowel disease. Retrieved August 19, 2020, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3616441/

- Canakis, A., & Qazi, T. (2020, January 30). Sleep and Fatigue in IBD: An Unrecognized but Important Extra-intestinal Manifestation. Retrieved August 02, 2020, from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11894-020-0746-x

- Cappuccio, F. P., Taggart, F. M., Kandala, N., Currie, A., Peile, E., Stranges, S., & Miller, M. A. (2008, May). Meta-analysis of short sleep duration and obesity in children and adults. Retrieved August 01, 2020, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2398753/

- Chagas, M. N., Crippa, J. S., Zuardi, A. W., Hallak, J. E., Machado-de-Sousa, J., Hirotsu, C., . . . Andersen, M. (2013, January 23). Effects of acute systemic administration of cannabidiol on sleep-wake cycle in rats. Retrieved November 11, 2020, from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0269881112474524

- Chan, D., Robbins, H., Rogers, S., Clark, S., & Poullis, A. (2013, July 31). Inflammatory bowel disease and exercise: Results of a Crohn’s and Colitis UK survey. Retrieved August 22, 2020, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28839750/

- Chang, A., Aeschbach, D., Duffy, J. F., & Czeisler, C. A. (2015, January 27). Evening use of light-emitting eReaders negatively affects sleep, circadian timing, and next-morning alertness. Retrieved September 17, 2020, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4313820/

- Chen, M., Mei, Q., Xu, J., Lu, C., Fang, H., & Liu, X. (2011, July 08). Detection of melatonin and homocysteine simultaneously in ulcerative colitis. Retrieved August 19, 2020, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0009898111003706

- Chennaoui, M., Arnal, P. J., Sauvet, F., & Leger, D. (2014, June). Sleep and exercise: A reciprocal issue? Retrieved August 23, 2020, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264085860_Sleep_and_exercise_A_reciprocal_issue

- Chueh, K., Guilleminault, C., & Lin, C. (2019, June). Alcohol Consumption as a Moderator of Anxiety and Sleep Quality. Retrieved September 24, 2020, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6554008/

- Clrs, P., Bts, B., Gonçalves Reis, C. E., & Jg, D. (2017, October). Consumption of coffee or caffeine and serum concentration of inflammatory markers: A systematic review. Retrieved November 10, 2020, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320178771_Consumption_of_coffee_or_caffeine_and_serum_concentration_of_inflammatory_markers_A_systematic_review

- Codoñer-Franch, P., & Gombert, M. (2018, October 14). Circadian rhythms in the pathogenesis of gastrointestinal diseases. Retrieved August 19, 2020, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6189841/

- Cohen, S., Doyle, W. J., Alper, C. M., Janicki-Deverts, D., & Turner, R. B. (2009, January 12). Sleep habits and susceptibility to the common cold. Retrieved August 01, 2020, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19139325/

- Conley, S., Proctor, D. D., Lehner, V., Jeon, S., & Redeker, N. S. (2020, June 9). The Feasibility of Measuring Sleep and Circadian Characteristics in Adults with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Retrieved November 13, 2020, from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0193945920933926

- Costa, R. J., Snipe, R. M., Kitic, C. M., & Gibson, P. R. (2017, June 07). Systematic review: Exercise‐induced gastrointestinal syndrome-implications for health and intestinal disease. Retrieved August 22, 2020, from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/apt.14157

- Cutolo, M. (2016, March 18). Glucocorticoids and chronotherapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Retrieved August 26, 2020, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4800804/

- Dawson, D., & Campbell, S. S. (1991, November 01). Timed Exposure to Bright Light Improves Sleep and Alertness during Simulated Night Shifts. Retrieved September 19, 2020, from https://academic.oup.com/sleep/article/14/6/511/2742848

- Deboer, T. (2018, March 01). Sleep homeostasis and the circadian clock: Do the circadian pacemaker and the sleep homeostat influence each other’s functioning? Retrieved July 31, 2020, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2451994417300068

- Decety, J., Bartal, I., Uzefovsky, F., & Knafo-Noam, A. (2016, January 19). Empathy as a driver of prosocial behaviour: Highly conserved neurobehavioural mechanisms across species. Retrieved August 01, 2020, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4685523/

- Demanuele, C., James, C. J., & Sonuga-Bark, E. J. (2007, December 10). Distinguishing low frequency oscillations within the 1/ f spectral behaviour of electromagnetic brain signals. Retrieved July 25, 2020, from https://behavioralandbrainfunctions.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1744-9081-3-62

- Devenney, L. E., Coyle, K. B., Roth, T., & Verster, J. C. (2019, May 27). Sleep after Heavy Alcohol Consumption and Physical Activity Levels during Alcohol Hangover. Retrieved September 24, 2020, from https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/8/5/752/htm

- Dhir, S., Tarasenko, M., Napoli, E., & Giulivi, C. (2019, March 22). Neurological, Psychiatric, and Biochemical Aspects of Thiamine Deficiency in Children and Adults. Retrieved November 10, 2020, from https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00207/full

- Di Milla, L., Vandelanotte, C., & Duncan, M. J. (2013, April 14). The association between short sleep and obesity after controlling for demographic, lifestyle, work and health related factors. Retrieved August 01, 2020, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23419528/

- D’Incà, R., Varnier, M., Mestriner, C., Martines, D., D’Odorico, A., & Sturniolo, G. C. (1999, April). Effect of moderate exercise on Crohn’s disease patients in remission. Retrieved August 22, 2020, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10379481/

- Ellenbogen, J. M. (2005, April 12). Cognitive benefits of sleep and their loss due to sleep deprivation. Retrieved July 31, 2020, from https://n.neurology.org/content/64/7/E25.full

- Ensrud, K. E., Blackwell, T. L., Ancoli‐Israel, S., Redline, S., Yaffe, K., Diem, S., . . . Stone, K. L. (2006, September 20). Use of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors and Sleep Disturbances in Community‐Dwelling Older Women. Retrieved September 30, 2020, from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00880.x

- Eswaran, S. L., Chey, W. D., Jackson, K., Pillai, S. G., Chey, S. W., & Han-Markey, T. (2016, April). A Low FODMAP Diet Improves Quality of Life, Reduces Activity Impairment, and Improves Sleep Quality in Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome andDiarrhea: Results From a U.S. Randomized, Controlled Trial. Retrieved August 8, 2020, from https://www.soscuisine.it/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/A-Low-FODMAP-Diet-Improves-QOL-…-RCT.pdf

- Everson, C. A., & Toth, L. A. (2000, April 01). Systemic bacterial invasion induced by sleep deprivation. Retrieved August 16, 2020, from https://journals.physiology.org/doi/full/10.1152/ajpregu.2000.278.4.R905

- Farhadi, A., Banan, A., Van De Kar, L. D., Shaikh, M., & Keshavarzian, A. (2003, September). Exaggerated response to physiological stress in patients with IBD; a possible contributing factor in the pathogenesis of IBD. Retrieved August 18, 2020, from https://search.proquest.com/openview/b738bac9417bcae546134643546d29d0/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=2041977

- Fernandez-Mendoza, J., Baker, J. H., Vgontzas, A. N., Gaines, J., Liao, D., & Bixler, E. O. (2017, March). Insomnia symptoms with objective short sleep duration are associated with systemic inflammation in adolescents. Retrieved August 16, 2020, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5316336/

- Flaman, Z., Pellechia-Clarke, S., Bailey, B., & McGuigan, M. (2001, February 1). Unintentional exposure of young children to camphor and eucalyptus oils. Retrieved November 11, 2020, from https://academic.oup.com/pch/article/6/2/80/2666678

- Fobian, A. D., Rouse, J., Stager, L. M., Long, D., Schwebel, D. C., & Avis, K. T. (2020, March 28). Effects of sleep deprivation and text messaging on pedestrian safety in university students. Retrieved August 15, 2020, from https://academic.oup.com/sleep/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/sleep/zsaa057/5813760

- Ford, A. C., Sandborn, W., Khan, K. J., Hanauer, S., Talley, N. J., & Moayyedi, P. (2011, April). Efficacy of Biological Therapies in Inflammatory Bowel… : Official journal of the American College of Gastroenterology: ACG. Retrieved August 27, 2020, from https://journals.lww.com/ajg/Abstract/2011/04000/Efficacy_of_Biological_Therapies_in_Inflammatory.12.aspx

- Francis, G., Bishop, L., Luke, C., Middleton, B., Williams, P., & Arendt, J. (2008, June 28). Sleep during the Antarctic winter: Preliminary observations on changing the spectral composition of artificial light. Retrieved September 17, 2020, from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00664.x

- Frank, S., Gonzalez, K., Lee-Ang, L., Young, M. C., Tamez, M., & Mattei, J. (2017, July 24). Diet and Sleep Physiology: Public Health and Clinical Implications. Retrieved August 13, 2020, from https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2017.00393/full

- Furukawa, Y., Cook, I. J., Panagopoulos, V., McEvoy, R. D., Sharp, D. J., & Simula, M. (1994, November). Relationship between sleep patterns and human colonic motor patterns. Retrieved August 08, 2020, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7926501/

- Föh, B., Schröder, T., Oster, H., Derer, S., & Sina, C. (2019, April 26). Seasonal Clock Changes Are Underappreciated Health Risks-Also in IBD? Retrieved August 26, 2020, from https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2019.00103/full

- Garland, S. N., Johnson, J. A., Savard, J., Gehrman, P., Perlis, M., Carlson, L., & Campbell, T. (2014, June 18). Sleeping well with cancer: A systematic review of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in cancer patients. Retrieved September 20, 2020, from https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2014-30527-001