What is Turmeric?

Turmeric is one of the many common names for the plant species Curcuma longa and the spice produced from it. Depending on what language you speak and where you live it might also be called things like curcuma, haldi, manjal, halad, dilaw, ukon, or gurkmeja. Turmeric is part of the Zingiberaceae plant family and is closely related to the plant and spice known as ginger.

Turmeric is a perennial, flowering, and herbaceous plant that requires warm temperatures and a lot of annual rainfall to survive. Due to these requirements, turmeric only grows easily in very tropical parts of the world, primarily Southeast Asia. The majority of turmeric is cultivated in India with exports exceeding US $236 million in 2018 (Centre for Advance Trade Research, 2019). Turmeric is grown for its leaves (pictured below) and rhizome (pictured above). Rhizomes are specialized stalks that grow into the ground and produce roots. Another very common term for rhizomes is rootstalks. Many well-known plants produce rhizomes including ginger, bamboo, asparagus, hops, and irises.

During harvesting, the leaves and rhizomes are collected and processed. Some of the leaves are simply washed, dried, and shipped to be sold fresh for culinary use. A minority of the leaves are dried and used in teas or as a spice. The rhizomes require much more processing, and there are a number of different techniques used. The basic steps in the processes are boiling or steaming the rhizomes, transferring them to alkaline water (normally baking soda is used) and boiling them again, drying them in the sun, and polishing the rough outer layer until it is smooth. Some rhizomes are sold whole and others are ground into a powder before being sold. Due to the large variety of techniques for processing turmeric and a lack of regulation, dangerous chemicals and dyes are sometimes used in the processing. It is very important you only purchase turmeric from extremely transparent and reputable suppliers.

The leaves and rhizomes of turmeric are used for a variety of purposes including seasoning and flavoring, dyeing, medical therapies, ceremonies, and chemical indicators (goldenrod paper). The use of turmeric by the Indus Valley Civilization dates back as far as 4,000 years ago around 3500 BC (Abraham, 2016). This Bronze-Age civilization thrived along the Indus River in what is now modern-day Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India. The Indus people frequently mixed turmeric with ginger and garlic to produce curries (Abraham, 2016). It is also assumed they used turmeric as a dye for fabrics but there is a lack of evidence to confirm this.

It did not take long for turmeric to be utilized in a medical context with how popular it was as a spice and dye. The first records of medicinal use of turmeric are from the Sushruta Samhita; an ancient Sanskrit text that detailed medications and surgical techniques from around 1000 BC to 500 AD. Turmeric became an integral part of the traditional Indian medicine known as Ayurveda. In Ayurvedic texts, turmeric is listed as a treatment for numerous skin, stomach, and joint problems.

Turmeric’s popularity has not faded over the thousands of years since it was first used by humans. To this day, turmeric is still used in cooking to change the flavor and color of foods like mustard, curries, and dairy products. It also continues to be commonly used to dye fabric and make goldenrod paper for use as a chemical indicator. In 2018 turmeric was the second most sold herbal supplement; only being outsold by cannabidiol (Smith, T., 2019). For several years turmeric was the top-selling herbal supplement in the USA with sales in the tens of millions of dollars each year. Many people speculate this is due to the supposed anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative properties of turmeric (similar to cannabidiol). With the increasing prevalence of inflammatory diseases like inflammatory bowel diseases (Alatab, 2020), rheumatic diseases, and auto-immune conditions many people may be attempting to use turmeric to alleviate their inflammation and other associated symptoms.

Turmeric’s Composition and why it’s Yellow

Turmeric consists mostly of starches and fibers with a small amount of protein, fat, and minerals. It is not much different in composition than other plant rhizomes with the exception of its essential oil and a group of chemicals called curcuminoids. These two groups of chemicals are responsible for the unique flavor, scent, color, and biological activity of turmeric.

Curcuminoids

The compounds inside turmeric responsible for its beautiful, vibrant, color and some of the medicinal effects are called curcuminoids. There are many different curcuminoids that are slightly different from each other, but all share a similar chemical shape. The yellow color they produce is so vibrant that turmeric is frequently referred to as “Indian saffron.” The most abundant and well-known of these curcuminoids in turmeric is called curcumin (despite the similarity in names the spice cumin does not contain any curcumin!). The curcumin content of turmeric grown in India and Sri Lanka has been measured between 0.3% to 8.6% with averages being between 3.1 to 4.8% (Dixit, 2009; Tayyem, 2006). Without standardization and regulation, the curcumin content of turmeric is unreliable amongst unbranded suppliers. Even worse, 17% of unbranded turmeric powders tested positive for Metanil Yellow (Dixit, 2009). This dye is also known as Acid Yellow 36 or D&C Yellow No.1 and is typically used for dyeing fabrics. It is extremely unsafe for human consumption. Metanil Yellow has been known to promote cancer in humans and cause testicular damage, cancer, and hematological problems in animals (Jain, 2009). These types of adulterants are commonly used to mimic the vibrant color produced by curcuminoids. The quality of turmeric is gauged by its color, so lackluster turmeric with a low curcuminoid content is invaluable and sometimes unsalable. A study on curcumin content and color differences in turmeric confirmed this with the lower-curcumin samples appearing more orange-yellow compared to the bright, vibrant yellow associated with curcumin (Madhusankha, 2018).

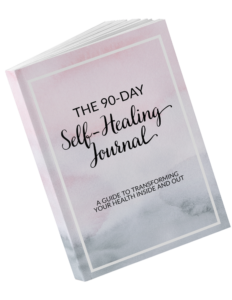

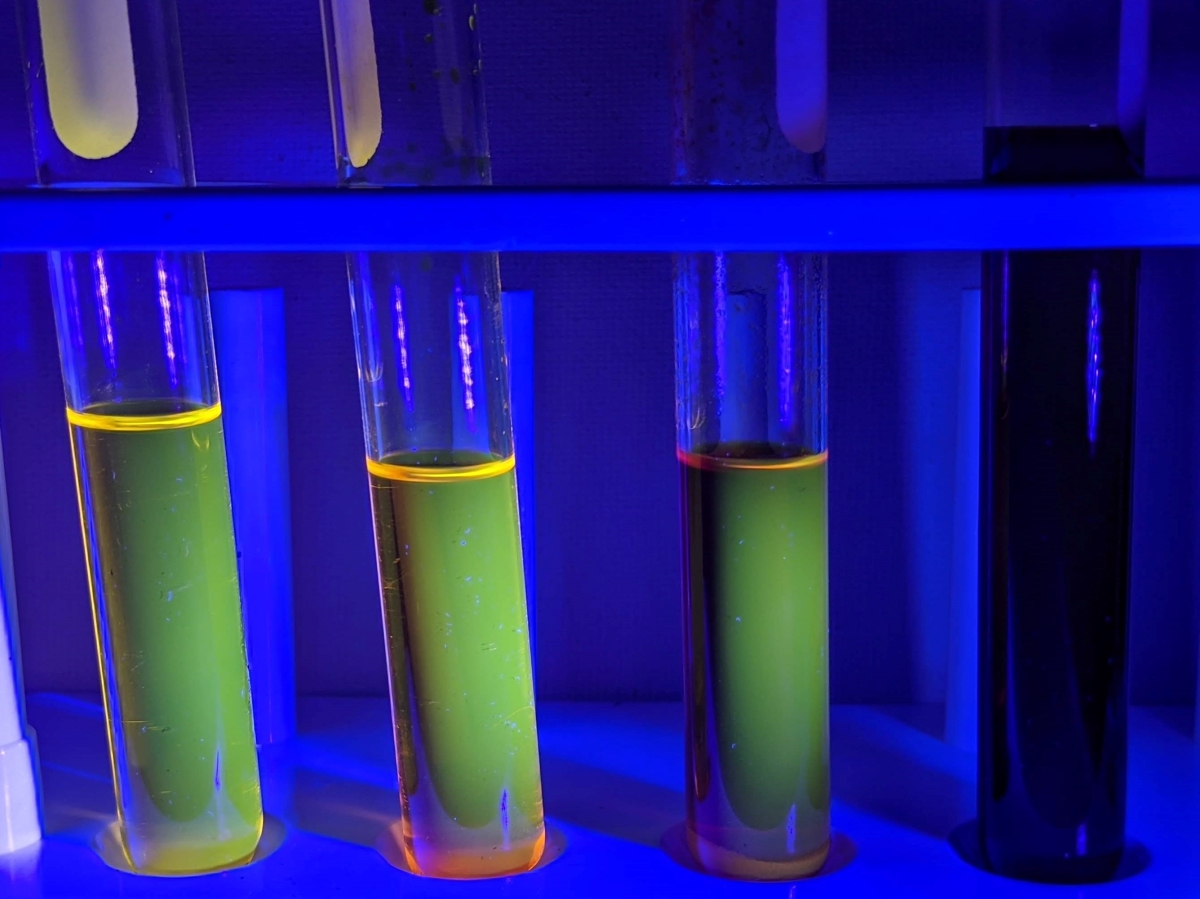

(From left to right: curcuminoids in ethanol, curcuminoids adulterated with azo dyes in ethanol, curcuminoids in ethanol made basic with sodium bicarbonate, rosocyanine (created when curcuminoids react with boric acid) in ethanol)

(Curcuminoids displaying various degrees of fluorescence when exposed to ultraviolet light – azo dyes can increase the glow and high pH or the presence of metal ions can decrease the glow.)

Terpenes:

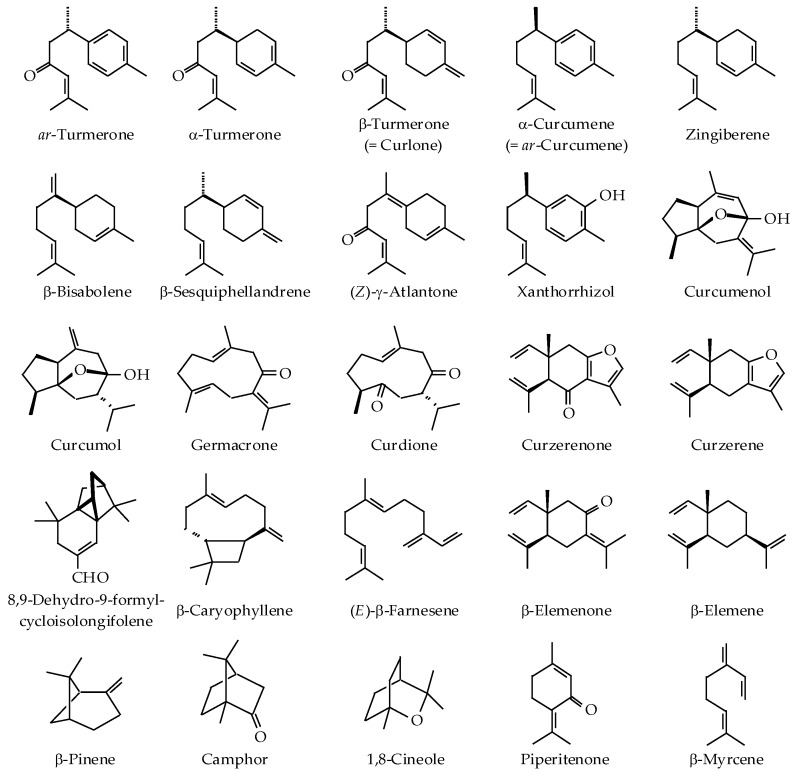

(Figure 1 – Dosoky, 2018)

(Figure 1 – Dosoky, 2018)

Like other aromatic plant products, turmeric contains essential oil. The essential oil of turmeric is complex and consists of a group of chemicals that do not dissolve in water. Part of the essential oil is a group of chemicals known as terpenes. Terpenes easily evaporate, typically have strong odors, and are used in flavorants, perfumes, cosmetics, medicine, and chemical synthesis. Some of them are unique to turmeric, and some are commonly found in other plant species. Terpenes can have medicinal effects on people separate from the main active ingredients found in the plant they come from. They can also change the effects of the main active ingredient by influencing how it reacts with your body (Afzal, 2013). The terpenes in turmeric could prove to be just as important if not more important than curcuminoids in creating new medications. The terpenes found in turmeric have been investigated in animal studies for several different conditions (Dosoky, 2018). They helped improve hyperlipidemia, hyperglycemia, and diabetic outcomes in rats and hamsters fed a high-fat diet (Ling, 2012; Singh, V., 2013). In an animal model of rheumatoid arthritis, turmeric essential oil helped prevent joint damage (Funk, 2010; Singh, G.,2010). The oil also has hematological effects which help prevent the damage from arterial injuries (Singh, V., 2015). One of the terpenes, ar-turmerone (pictured above), even acts as an antidote to two different species of snake venom (Ferreira, 1992).

Adulterants and Contaminants:

(Wheat Flour – A Common Bulking Agent)

It is very important to mention some of the extra things that are sometimes found in lower-quality turmeric sources. Most of the adulterants found in turmeric are dyes being used to fake the appearance of turmeric with a high curcuminoid content. Unfortunately, there are also several adulterants used to bulk up the volume and weight of the turmeric being sold. Additionally, some other contaminants encountered during the production of turmeric could be present in the final product without being intentionally added.

- Dyes – The most commonly found adulterant in turmeric, dyes are used to fake the appearance of high-quality turmeric. Most of them are a special type of dye called azo dyes. Some of the azo dyes have chemical bonds that are similar in shape and function to the bonds in curcuminoids. This similarity allows them to mimic the intense yellow and orange hues of turmeric (General Introduction to the Chemistry of Dyes, 2010). This is necessary to make low-quality turmeric more salable, and to hide the presence of other adulterants that dull the vibrant yellow and orange color.

- Bulking Agents – These are the second most commonly found adulterants in turmeric powders. The bulking agents are typically other Curcuma species that are not as valuable, or cheap starches and sugars like wheat flour and dextrose. A perfect example of the less valuable species is Curcuma zedoaria, which is also known as white turmeric. White turmeric is a member of the Zingiberaceae family of plants that surprisingly tastes more similar to ginger than turmeric. The smell of white turmeric is described as the same as the smell of turmeric yet more mango-like. As its name implies, white turmeric looks extremely similar to turmeric but with a color more similar to ginger. Fresh it appears white to yellow, and as a dried powder it looks light brown to very light tan. There are no known negative health effects from consuming white turmeric or starches and sugars. However, unscrupulous turmeric suppliers will sometimes use dangerous azo dyes or lead chromate to hide their presence in turmeric powders that have been adulterated to increase bulk (Dhakal, 2019). Allergies are also a concern for those who have sensitivities to wheat flour or nuts as both have been discovered in turmeric samples (Cardellina, 2020).

- Contaminants – These constituents are not intentionally introduced to the turmeric being supplied. These assorted contaminants are normally picked up as part of the manufacturing process or improper storage and handling. They include things like misidentified species that were introduced to a turmeric crop and harvested with the turmeric or hybridized with it (Hayakawa 2011), heavy metals absorbed by the plants (Vineeth, 2014), and microbiological organisms that somehow cross-contaminated the turmeric from improper storage and handling (Hara-Kudo, 2006; Risk Profile: Pathogens and Filth in Spices, 2017). Ingestion of turmeric powders with these contaminants can cause a plethora of serious health problems. Unfortunately, there is not much the consumer can do to prevent being exposed to them, as even scientists have struggled to produce a cheap, widely available testing kit for the variety of adulterants and contaminants encountered (Sasikumar, 2019). Careful sourcing and vetting of suppliers have remained one of the most effective methods for consumers to protect themselves from contaminants.

Conditions That Might Benefit From Turmeric

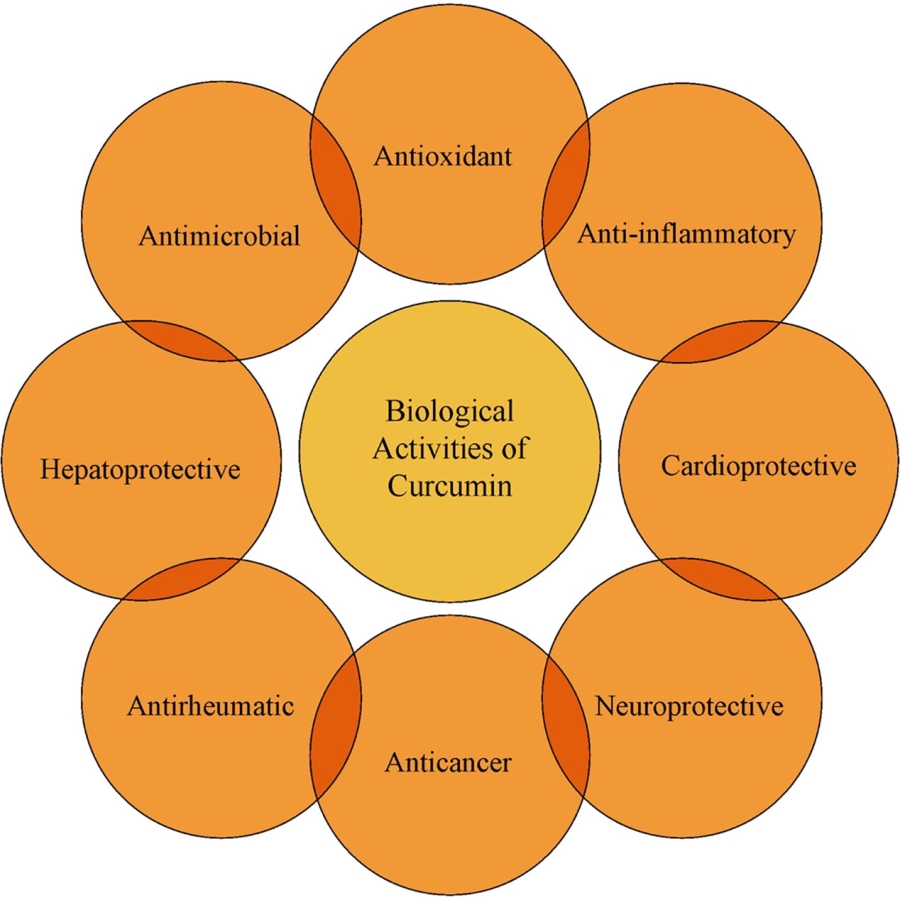

Turmeric has been suggested as a treatment for almost any known illness. Most of these claims do not have much merit, however, there are some that are being invested further as potential treatments. Some of the more promising medical uses of turmeric focus on rheumatoid arthritis, irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel diseases, metabolic disorders, cardiovascular conditions, cancer, chronic pain, and dermatological conditions (Patel, 2019; Sharifi-Rad, 2020). With turmeric’s extensive history as a traditional medicine and the absolutely massive amount of research on the subject, it is helpful to analyze the data statistically. One of the most common methods to do this is through meta-analyses of systematic reviews. First, a systematic review of all the available research studies done on a subject is conducted. This is how all the information and data is collected. Then a statistical analysis is performed on the systematic review to consolidate all that information into a more uniform conclusion (Haidich, 2010). This process of analyzing and consolidating is known as a meta-analysis. The meta-analyses can help you interpret large amounts of data and create more accurate statistical averages. Sometimes they even facilitate the discovery of patterns that are only observable with a large enough sample size. For example, one thousand studies involving ten patients might not discover what one study involving ten thousand patients would. By interpreting the combined data from systematic reviews these meta-analyses act as a very valuable tool in making judgments about research. However, the limitations of meta-analysis and systematic reviews should be noted, there are several issues that can impair their reliability and accuracy (Ahn, 2018). With these limitations in mind, several systematic reviews and meta-analyses have found slight benefits to using turmeric.

(Figure 3 – Sharifi-Rad, 2020)

Inflammatory Bowel Diseases – There have been several systematic reviews and meta-analyses done on the various types of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD). This is one of the more well-studied aspects of turmeric’s use as a medical compound. A meta-analysis of curcuminoids’ effects on ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease yielded slightly positive results for both but stated uncertainty due to the lack of quality research (Alvares Goulart, 2020). The results are more controversial for Crohn’s disease because of significant biases in many of the studies. Further studies are needed to clarify the most effective formulations, route of administration, and doses for both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease (Coelho, 2020).

Although the evidence for Crohn’s disease is biased, there were some positive results found in another systematic review of the comparison between curcumin and infliximab. The review found a slight decrease in interleukin-1β (IL-1β) with curcumin treatment in combination with infliximab in comparison to infliximab alone (Schneider, 2017). This decrease in IL-1 is associated with better long-term efficiency with infliximab, however, the authors provide no direct evidence of causation. The high rates of infliximab resistance and the association between curcumin and lower IL-1 levels improving responses to infliximab makes turmeric worth investigating. Unfortunately, the research is very far from understanding how curcumin might be helping patients respond to infliximab for longer periods.

There is better research promoting the use of turmeric and curcuminoids for the treatment of ulcerative colitis. A systematic review found consistently positive results in randomized controlled clinical trials (RCTs) for curcuminoid use as a complementary therapy in ulcerative colitis. Five out of the six RCTs included in the systemic review were positive; with results ranging from symptom reduction to induction of remission (Coelho, 2020). The major hurdle posed by the authors was the inconsistency with curcuminoid formulation, dose, and duration of treatment as well as small sample sizes. Another meta-analysis has confirmed the findings of Coelho et al. and suggests curcuminoids should be focused on as a complementary treatment for ulcerative colitis. Curcumin and mesalamine combination therapy was found to be three times more effective than placebo (Chandan, 2019).

Irritable Bowel Syndrome – Another meta-analysis suggests further investigation of the constituents of turmeric for Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS). Although the results were only slightly promising, this study did suggest the use of turmeric as an experimental adjunct to current therapies. Despite turmeric use being found to be statistically insignificant, it was about as effective as placebo. This limited efficacy is attributed to the suspected anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties of turmeric. Another possibility for the improvement in IBS symptoms is turmeric’s effects on the gut microbiome. Similar to the systematic review on cancer treatments, no negative effects were reported in any of the studies. In light of the low toxicity of turmeric (despite low efficacy) the meta-analysis supports its use for IBS (Ng, 2018).

Rheumatoid arthritis – One of the most substantially positive meta-analyses showed an improvement in rheumatoid arthritis patients. The authors stated the evidence was very limited in size and had several issues, but it supports further research and utilization of turmeric as a supplement for rheumatoid arthritis. There is some speculation that this might be due to one of the many constituents of turmeric or its metabolites’ ability to block inflammation and act as antioxidants. (Daily, 2016).

Pain – A few studies have been done to determine the effects of curcuminoids on pain levels. A meta-analysis of these studies found that curcuminoids were a statistically significant analgesic (pain-reliever) and well-tolerated. Although the total number of subjects was small (606) the evidence was considered free of publication bias. The authors suggest strongly controlled studies to further determine the efficacy and safety of long-term use of curcuminoids for pain relief (Sahebkar, 2015).

Dermatological Conditions – Turmeric has been used orally and topically for a variety of skin conditions. A meta-analysis of eighteen studies involving turmeric as a treatment for acne, alopecia, atopic dermatitis, facial photoaging, oral lichen planus, pruritus, psoriasis, radiodermatitis, and vitiligo found slight evidence to suggest turmeric as a possible treatment for dermatological conditions (Vaughn, 2016). Like other meta-analyses, this one mentions the limitations of the current studies. Many of the studies did not provide strong, quality data to definitively draw conclusions from. This makes it extremely difficult to determine the efficacy and mechanisms of turmeric in these conditions.

Cancer – Although there is extremely limited evidence for its use in cancer, turmeric has shown slight increases in survivability in patients receiving chemotherapy. The exact mechanisms are not fully understood, but the beneficial actions on cancer patients are attributed to the anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and metabolic effects of turmeric. A systematic review on turmeric use for enhancing chemotherapy found no reports of negative side effects and suggests using it as an adjunct to current cancer treatments (Mansouri, 2020). With no negative side effects, even a slight possibility of improvements is an acceptable risk to benefit ratio for more serious cancers.

Metabolic/Cardiovascular – There have been several systematic reviews and meta-analyses done on the cardiovascular and metabolic effects of turmeric, especially in relation to metabolic disorder. Turmeric was able to inconsistently improve certain aspects of dyslipidemia in metabolic disorder. This might lead to improvements in systolic blood pressure for those who suffer from high blood pressure due to metabolic disorders. The evidence to confirm the benefits of turmeric was considered too inconsistent by most of the systematic reviews and meta-analyses (Hadi, 2019; Qin, 2017; Yuan, 2019). However, one meta-analysis states curcuminoid supplementation improves some (but not all) of the factors involved in metabolic disorder (Azhdari, 2019).

How does Turmeric Work?

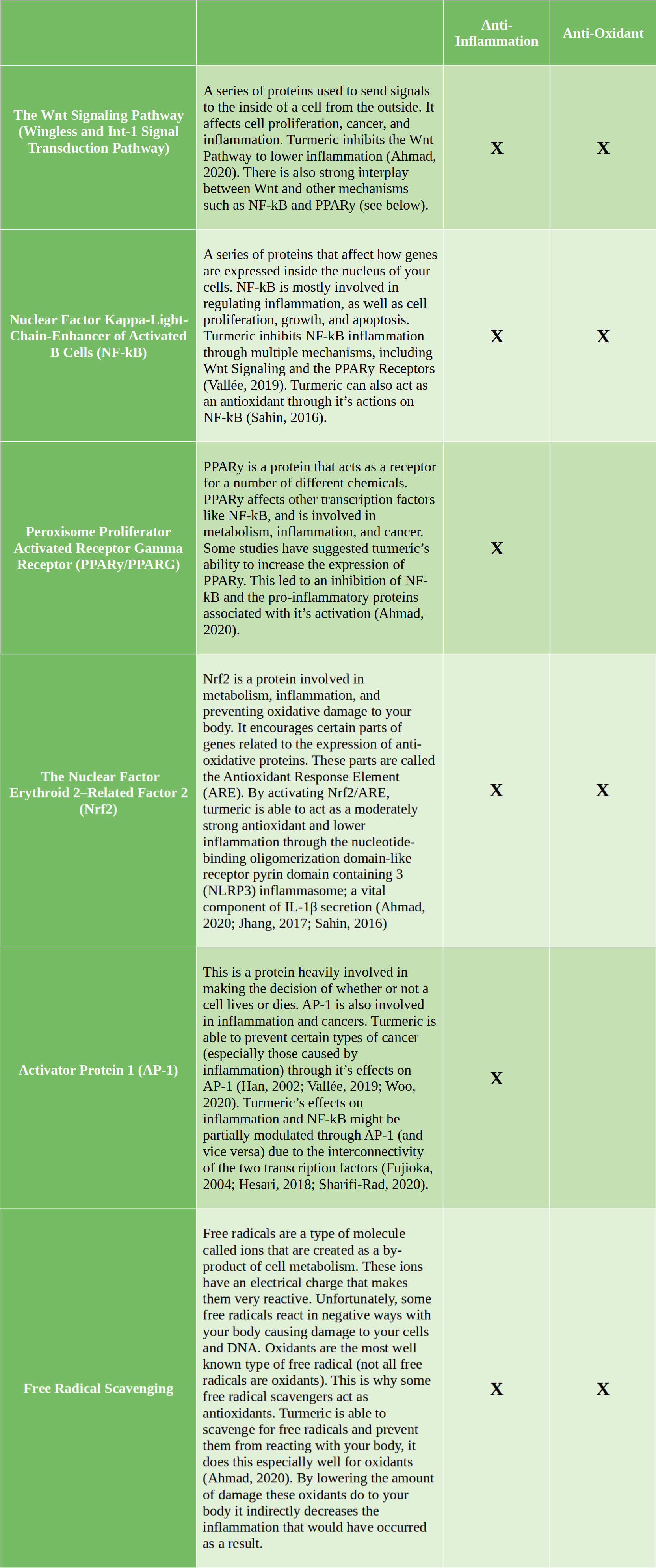

Turmeric interacts with many different parts of your body in complicated ways. This is expected because the chemicals found in turmeric are extremely diverse, and each one is capable of a multitude of reactions. With this in mind, it is easier to focus on specific health effects of turmeric rather than everything it does. The most important and readily recognized uses of turmeric are inhibiting inflammation and oxidative damage. These effects are important for many conditions including inflammatory bowel diseases, cancer, rheumatic diseases, pain, metabolic issues, and cardiovascular conditions. Some of these mechanisms are still being confirmed and explored (much of the research is in its early stages), but there is significant evidence to suggest they are involved in turmeric’s anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties.

What is so Controversial About These Promising Results?

It might seem fairly straightforward and simple using turmeric as medicine if there is research to support it. The research appears to show it is medically beneficial, cheap, abundant, and without any major safety concerns. This should be a perfect situation for producing a lot of cheap and effective medicine, but issues with both turmeric and the medical industry have caused the opposite to happen. There have been no successful attempts at creating a medication from turmeric, and many experts are abandoning further efforts due to concerns over costs and failure. Some of them argue that turmeric will waste other researchers’ time if it continues to be studied through traditional reductionist methods that do not account for social and cultural context, polypharmacology, synergies, and unknown impurities or metabolites (Nelson, 2017). Several other studies have also emphasized the limitations of curcuminoids and turmeric and their possible inefficacy in certain conditions. A systematic review and meta-analysis of markers of systemic inflammation measured in randomized-controlled trials using curcuminoids showed no difference in the markers (White, 2019). A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of curcumin as an adjunct to antidepressant treatments found it to be insignificant and no better than placebo (Bergman, 2013). Another double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of curcumin for Alzheimer’s disease also failed to show any difference from the treatment after 24 weeks (Ringman, 2012).

There are several obstacles posed by turmeric and its components that have seriously (and repeatedly) contributed to the debate of its appropriateness as a candidate for drug development:

Turmeric is a Complex Mixture – Turmeric, like many other botanical products, is a complex mixture of different chemicals such as terpenes, phytochemicals, sugars, fats, proteins, and other complex carbohydrates. Cultivation, genetics, and processing methods can all affect the constituents of botanical products. If the end product is not properly characterized it can lead to inconsistencies, confusion, and irreproducible study results (Kellogg, 2019). Typically these problems with complexity and inconsistency are partially resolved through standardization.

Lack of Standardization – There can be little to no standardization without well-established methods being used to identify turmeric, its adulterants, and the active ingredients responsible for its medical effects. Many scientists have started studying the mechanisms of specific compounds in turmeric (like curcuminoids) without confirming what the chemical composition of those compounds consists of. This is important in determining whether the studied compounds are what are typically used by consumers reporting benefits from turmeric use, and whether or not they are actually the active ingredients in turmeric. Some have suggested this poor quality of research is supported by pressure to find positive results for financial gain, inexperienced researchers without a strong understanding of medicinal chemistry, and simple laziness. Regardless of the causes, lack of standardization continues to plague turmeric and curcuminoid research. It contributes to the irreproducibility of results, the lack of organization between researchers, and the controversy of turmeric’s suitability in medicine. It is one of the most prevalent and crippling issues in turmeric research.

Turmeric is Chemically Unstable – Turmeric and some of the compounds found in it like curcuminoids are infamously unstable. For example, curcumin is unstable in water and even more in acidic water. This means it would never make it past your stomach without breaking down before your body could absorb it. The instability also makes it very difficult for curcumin to work as a drug inside your body because it is too quickly broken down or metabolized if it is absorbed. Simply exposing curcumin to quick bursts of sunlight can degrade it within minutes and has made working with it slightly difficult in a lab setting (Priyadarsini, 2014). Essentially, nobody can work with curcuminoids if they keep breaking into pieces every step of the process.

Turmeric is too Chemically Reactive – One reason for the instability of curcuminoids is how chemically reactive they are. Some amount of reactivity is desirable and necessary to make a drug as it will need to react with your body to have an effect. However, too much reactivity or unpredictable and uncontrollable reactivity can cause issues with a drug’s development, dosing, allergies, side effects, and cancers.

There are a variety of useful and problematic reactions that curcuminoids are capable of. For example, curcumin is known to chelate (bond in several places with) iron and form metal complexes with most known metals (Priyadarsini, 2014). These reactions can cause misleading results in studies by interfering with chemicals involved in the research and introducing heavy metal contaminants (Baell, 2018). Curcumin is also fluorescent which some researchers argue could interfere with some research methods (Nelson, 2017). Although this theory has not been adequately tested and other researchers say it is fluorescent, but not in an interfering manner (Bahadori, 2017). Nonetheless, curcuminoids are considered pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS) by many researchers (Nelson, 2017). Pan-assay interference compounds are drug candidates that interfere with several different drug development techniques or react in ways known to cause false positives. Normally drug candidates designated as PAINS are abandoned and not further explored due to the complexity, expense, and high risk of exploring them.

There is some debate about PAINS designations, with the authors who coined the term PAINS even admitting its limitations (Baell, 2018). One study found 87 FDA-approved medications that could have been designated as PAINS, and possibly never developed had they been ignored. The authors cautioned against using PAIN designations as the sole determining factor in deciding whether or not to develop a drug candidate (Capuzzi, 2017). As useful of a tool as PAINS designation can be in preventing wasted resources it can still lead to errors in judgment.

Incompatibilities with Drug Development Techniques – Typically substances need to meet certain specifications in order to be developed into drugs. Modern pharmaceutical companies and medicinal chemists are extremely methodical in the processes used to develop new drugs. They do this to ensure complete control over as many variables as possible. This helps lower risks, prevent failures, and maximizes the potential of new drugs. These methodical processes also enable them to create very specific drugs that lead to the desired effects without many side effects. Anything that does not work in line with these processes is seen as a potential issue and undesirable.

An often forgotten dynamic of their jobs is to meet business goals and deadlines to remain profitable. If drug candidates are not able to satisfy the needs of the business (despite being medically effective) they are typically abandoned. For example, some rare conditions and diseases are not profitable to focus on because there are so few patients to pay for the treatment. This was such a serious barrier to drug development for these conditions that Congress passed the Orphan Drug Act. This was done to “amend the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act to facilitate the development of drugs for rare diseases and conditions, and for other purposes.” Another issue caused by economic and business factors is drugs that can not be patented are typically never developed. There have been very long discussions on the issue of unpatentable drugs and how they are desperately needed but not prioritized (Roin, 2013).

Some researchers claim substances like turmeric and curcuminoids do not work very well with some of the processes used to develop them into drugs. They suggest new models for the development of turmeric and curcuminoid drugs as a viable route to clinical use (Cavaleri, 2018). If further studies confirm the validity of their claims it could explain why so much previous research has failed to fully explain and show the medical benefits of turmeric. Some of which might be partially explained by simple errors in storage and other researchers’ failure to consider NF-kB inhibition (mentioned earlier) and polypharmacology (Bahadori, 2017). Turmeric and curcuminoids are very reactive and not very specific, which is normally incompatible with traditional drug manufacturing processes. However, some researchers see this polypharmacology as advantageous with more complicated diseases that involve many different mechanisms and systems cohesively. They claim that by causing NF-kB inhibition turmeric and its constituents like curcuminoids (or their metabolites) can act through multiple mechanisms to cause improvements in conditions like cancer, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, ulcerative colitis, and Crohn’s disease. (Cavaleri, 2018).

In regards to the patentability of turmeric and curcuminoids, many researchers suggest making modifications to them in order to create unique and patentable drugs that are equally or more effective in treating disease (Kurien, 2007; Rodrigues, 2019). While other’s have suggested not developing turmeric and curcuminoids into drugs, but rather focusing on the polypharmacology and medicinal benefits of the typical consumer use of turmeric (Nelson, 2017). There is evidence of the synergy of the different constituents found in plant products acting through multiple mechanisms to cause their beneficial effects (Wagner, 2010). This could explain why drug leads from turmeric and curcuminoids perform so poorly in studies, but perform better in real-life use. Regardless, as a variety of different techniques for turmeric and curcuminoids are tested, we will hopefully learn more about the limitations and strengths of the current and alternative drug development systems available.

Research Quality is Lacking and Possibly Fraudulent – The most controversial issue with turmeric and curcuminoid research is the questionable quality and possible fraud found in several of the studies. A very prominent researcher named Bharat Aggarwal had several dozen studies retracted (with even more being reviewed) because it was discovered that he was modifying and reusing images and data from other studies. With no way to confirm what was true and what was fraudulent the data from many of his studies are considered unreliable.

This was a devastating blow to the credibility of curcuminoids as a treatment for cancer and inflammation. Bharat Aggarwal had published at least 65 papers that were called into question after the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Research Integrity was notified by whistle-blowers. His motive was assumed to be financial due to him having published many different books about the medicinal effects of plants and spices as well as co-founding a pharmaceutical company called Curry Pharmaceuticals. A company that deceptively portrays Bharat Aggarwal’s previously discredited work as evidence for their claims that curcuminoids can treat psoriasis. They also tried to solicit six million dollars in startup funding. It is safer to assume anything Bharat Aggarwal is involved with is a scam and pseudoscientific rather than true scientific research. He has cast a horrible shadow of doubt and shame on previous curcuminoid research simply for financial benefit.

Advice for Using Turmeric

Although the controversy and limited evidence for turmeric and curcuminoids dissuade some from trying it as a supplement you might want to try it for yourself. It is generally safe to try, cheap to purchase, readily available at most stores, and can be used in a number of ways. From simply including it in your cooking to making your own capsules there are many options for supplementing with turmeric. These are some of the most important aspects of its use that you want to consider if you plan to start using turmeric, or if you already do use it:

- Finding a Good Supplier – The most important part of using turmeric as a supplement is finding a trustworthy supplier. Lack of standardization and limited regulation of the supply chain creates a significant difference between different suppliers. In one small study of nine different samples of turmeric powder, the curcumin content ranged from 0.98% to 2.48% (Tayyem, 2006). Several brands have even been recalled for dangerous amounts of lead contamination (Cowell, 2017).

There are several options to find a good supplier and protect yourself. Your first option is to do research on the brands you are considering buying. Most reputable suppliers will list information on their website explaining how they ensure quality and safety. Call the company if you do not see something you are specifically interested in. If researching brands is too time-consuming or overwhelming to you, there are services that review and test products for you. A well-known example of these services is Consumer Reports Incorporated. The services do typically cost money, but some provide in-depth reviews and tests of turmeric brands. A free alternative to check if the turmeric brand you currently have at home is safe to use is government recall websites. The Federal Drug Administration (FDA) and the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) both list recalls for turmeric supplements and food products on their websites.

- How to use Turmeric – Most people use turmeric orally as a cooking ingredient or as a dietary supplement. This can be done in a variety of ways by using turmeric as a dry spice, adding it to sauces, pastes, and oils, or taking it in tablets or capsules. The highest dose tested and found to be safe in humans is the equivalent of a 155lb (70kg) person consuming about two tablespoons of turmeric (4-10g) per day (Coelho, 2020). Consuming more than this amount could cause issues for individuals who are more sensitive to the possible side effects of turmeric. Luckily, the strong flavor of turmeric ensures taking too much is difficult. Even when taking turmeric in capsules and tablets it is difficult to take too much. Regardless of how safe turmeric is to consume orally, it is best to try a small amount first for several weeks before increasing the amount you take. This is to lower the risk of gastrointestinal discomfort or other side effects, and because the average amount of time for turmeric and curcuminoids to have an effect in studies is four to eight weeks (Coelho, 2020).

Some people prefer to use turmeric topically on their skin in various forms (pastes, lotions, ointments, etc.) The turmeric pastes, lotions, and ointments are made with ingredients commonly found in the kitchen like milk, flour, sugar, salt, spices, fats, oils, and honey. You can easily make your own custom formula and find dozens of other recipes for turmeric containing skin-products online. Keep in mind that when applied to the skin, the effects of the turmeric will be confined to your skin due to the limited absorption. Topical use of turmeric products has been suggested as a possible treatment for problems such as psoriasis, vitiligo, acne, and eczema (Vaughn, 2016). It can lead to stains and skin reactions, so it’s always best to start with only a small amount of the paste on a small area of skin. This allows you to test your skin’s sensitivity to turmeric as well as get practice with applying and removing the paste without making too much mess.

- Using Turmeric Alone or Mixed – Whether you decide to use turmeric orally or topically it is important to be aware of what you mix with it. There have been several studies showing different mixtures of turmeric and curcuminoids possess different effects and abilities to be absorbed (D’Ascola, 2019; Nasef, 2019). Consuming turmeric with other spices, foods, or medications can change how the turmeric affects your body as well as increase the amount of side effects from the mixture. Interestingly, mixtures of turmeric can also have a quicker effect on your body than pure turmeric does and might take less than four to eight weeks to show an effect (Coelho, 2020). There are many different drug interactions that can occur with turmeric consumption and some of them can be dangerous. Talk to your doctor if you currently take medication and wish to start using turmeric. Alternatively, if you are currently taking turmeric, always mention it to medical providers when they ask you if you take any medications or supplements.

- Preventing and Treating Stains – If you use turmeric for long enough you will eventually encounter issues with stains. Turmeric is notorious for staining almost everything it touches a yellow or orange color. Always be careful not to spill turmeric (do not use it in a windy area) and clean up any spills as quickly as possible. The longer turmeric rests on a surface the worse the stain will become. Soap and water will eventually remove the stains from skin, hair, and most clothing. If you are still having an issue removing the stain try placing it in the sunlight or underneath an ultraviolet (UV) light. Sunlight and UV light bulbs are very reliable in removing turmeric stains from fabrics and clothing. You can also apply an oxidizing agent like hydrogen peroxide to increase the effectiveness of UV light (Singh, 2009). Even stains caused by turmeric that is adulterated with azo dyes like metanil yellow or tartrazine should fade when exposed to hydrogen peroxide and UV light (Oancea, 2014; Sangari, 2014).

The Safety of Turmeric

Turmeric itself is “generally recognized as safe” by the Food and Drug Administration. It should not cause any significant health problems under normal conditions, but there are some safety issues that can arise. The conditions responsible for causing these health problems are: purchasing adulterated turmeric from an untrustworthy supplier, using turmeric in an unusual way or dose, and being at risk for an iron deficiency. The only significant health problem to occur while someone was taking turmeric under normal conditions is called autoimmune hepatitis (Lee, 2020). This is extremely rare and has only occurred a few times, it also quickly resolved in every case once the turmeric use was stopped. If using turmeric normally (and without an iron deficiency) the worst side effects are typically a headache, gas and discomfort, and mild skin rashes.

- Purchasing Unsafe Turmeric – If you are not careful purchasing turmeric you might accidentally purchase adulterated turmeric. Adulterated turmeric is dangerous and may cause serious health problems for two major reasons. The first is the possibility of ingesting azo dyes like Metanil Yellow or Sudan Red G. These dyes can cause cancer after enough repeated exposure through contaminated turmeric consumption. The second more immediate health risk is from wheat and nut allergies. Turmeric that has been mixed with wheat flour or powdered nuts can cause anaphylaxis and kill someone.

- Combinations, Large Doses, and Unusual Uses– Although turmeric is generally recognized as safe it can be dangerous if used in unusual ways or amounts. For example, The piperine found in black pepper has been associated with toxic effects when mixed with certain drugs (Coelho, 2020). Combining turmeric with black pepper can increase the amount of curcuminoids you absorb from the turmeric. This can cause issues because large doses of turmeric could result in liver toxicity and heart arrhythmias (Hu, 2011; Lombardi, 2020; Qiu, 2015; Ranjan, 2013). The most concerning issue of high doses is turmeric blocking the effect potassium has on your heart leading to a potentially lethal arrhythmia known as torsades de pointes (Kratz, 2017; Nogawa, 2011). Luckily torsades de pointes is rarely lethal, and it would require an abnormally large dose or unusual usage of turmeric. Typical doses and uses for turmeric are not going to have a strong enough effect by themselves to cause heart arrhythmias. However, it is important to speak with your doctor before trying turmeric if you suffer from Long QT Syndrome (LQTS) and have been told to avoid certain medications and foods that prolong your QT interval.

Other more unusual or experimental uses of turmeric have resulted in death. One unfortunate woman died from brain damage after suffering a heart attack shortly after being administered intravenous turmeric for eczema (Lasoff, 2017). It is not entirely clear if the turmeric directly caused her heart to stop from arrhythmia, or if it stopped indirectly from anaphylaxis, as both were feasible. Regardless of the exact mechanism that ended her life, the event served as an important reminder of the risks involved in experimental medical treatments. If you are considering using turmeric in large doses or in a novel manner, talk to your doctor or a knowledgeable medical provider first to get their professional opinion on the potential risks and how you can minimize them.

- Iron Deficiency – Like autoimmune hepatitis, this is a rare side effect of turmeric use. Most people will not develop anemia from eating turmeric. However, people who are predisposed to low iron levels should be very cautious consuming turmeric and speak to their doctor about it. Even healthy individuals could develop anemia from low iron levels if they consume large enough amounts of turmeric for an extended time (Smith, T. J., 2019). This is due to turmeric’s tendency to block iron absorption in your intestines (Nelson, 2017).

Conclusion

The debate surrounding turmeric as a potential drug candidate has continued for years, and will most likely not stop any time soon. We may never know with much certainty how and if turmeric improves health outcomes. However, with the good safety profile, low cost, and need for new drugs that treat inflammatory diseases and cancers turmeric provides a valuable option to explore. You should consider how it can be incorporated into your cooking and medical care. With its extensive history and variety of uses, turmeric continues to be one of the most popular spices and supplements in the world.

As research progresses further the mysteries surrounding turmeric will become less significant. We will eventually have a better understanding of the appropriate ways to use it medically and possibly create completely new medicines. If turmeric has existed as a part of humanity for thousands of years it is not going to simply disappear. Turmeric has become so intertwined with our art, food, medicine, and spirituality that naturally there will always be a place for it in our lives. The value of turmeric is unquestionable despite how controversial it may seem at times.

Judd Harper is an independent contractor, entrepreneur, and proud parent. He studies multiple subjects including medicine, organic chemistry, pharmacology, botany, and mycology. He successfully uses Complementary and Alternative Medicines (CAM’s) for his Crohn’s disease and advocates for health care reform and informed consent. He loves to spend time with his son, garden, listen to music, and learn new languages. He can be contacted at juddtharper@gmail.com with any questions or business solicitations.

References

- Abraham, S., Gullapalli, P., Raczek, T. P., & Rizvi, U. Z. (2016). Connections and complexity: New approaches to the archaeology of South Asia. London, England: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. doi:https://books.google.com/books?id=bRHjGtTUr3sC&printsec=copyright#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Afzal, A., Oriqat, G., Khan, M. A., Jose, J., & Afzal, M. (2013). Chemistry and Biochemistry of Terpenoids from Curcuma and Related Species. Retrieved April 07, 2021, from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/22311866.2013.782757

- Ahmad, R. S., Hussain, M. B., Sultan, M. T., Arshad, M. S., Waheed, M., Shariati, M. A., . . . Hashempur, M. H. (2020, May 11). Biochemistry, Safety, Pharmacological Activities, and Clinical Applications of Turmeric: A Mechanistic Review. Retrieved December 28, 2020, from https://www.hindawi.com/journals/ecam/2020/7656919/

- Ahn, E., & Kang, H. (2018, March 14). Introduction to systematic review and meta-analysis. Retrieved December 15, 2020, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5903119/

- Alatab, S., & GBD 2017 Inflammatory Bowel Disease Collaborators. (2020, January 1). The global, regional, and national burden of inflammatory bowel disease in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Retrieved November 28, 2020, from https://www.thelancet.com/journals/langas/article/PIIS2468-1253(19)30333-4/fulltext

- Alvares Goulart, R. D., Barbalho, S. M., Lima, V. M., Achete de Souza, G., Matias, J. N., Araújo, A. C., . . . Guiguer, É L. (2020, November 5). Effects of the Use of Curcumin on Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn’s Disease: A Systematic Review. Retrieved December 20, 2020, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33155879/

- Azhdari, M., Karandish, M., & Mansoori, A. (2019, April). Metabolic benefits of curcumin supplementation in patients with metabolic syndrome: A systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Retrieved December 19, 2020, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332177339_Metabolic_benefits_of_curcumin_supplementation_in_patients_with_metabolic_syndrome_A_systematic_review_and_meta-analysis_of_randomized_controlled_trials

- Baell, J. B., & Nissink, J. W. (2018, January 19). Seven-year Itch: PAN-ASSAY INTERFERENCE COMPOUNDS (PAINS) IN 2017-utility and limitations. Retrieved February 14, 2021, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5778390/

- Bahadori, F., & Demiray, M. (2017, September 14). A realistic view on “The essential medicinal chemistry of curcumin”. Retrieved February 24, 2021, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5601379/

- Bergman, J., Miodownik, C., Bersudsky, Y., Sokolik, S., Lerner, P. P., Kreinin, A., . . . Lerner, V. (2013, May). Curcumin as an add-on to antidepressive treatment: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, pilot clinical study. Retrieved February 06, 2021, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23673908/

- Capuzzi, S. J., Muratov, E. N., & Tropsha, A. (2017, March 27). Phantom pains: Problems with the utility of alerts For PAN-ASSAY INterference CompoundS. Retrieved March 05, 2021, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5411023/

- Cardellina, J. H., II. (2020). Turmeric Raw Material and Products Laboratory Guidance Document [PDF]. Austin: Botanical Adulterants Prevention Program. Retrieved December 4, 2020, from http://cms.herbalgram.org/BAP/LGD/BAPP-LGDs-Turmeric-FINAL.pdf

- Cavaleri, F. (2018, January 15). Presenting a new standard drug model for turmeric and its prized extract, curcumin. Retrieved March 07, 2021, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5820622/

- Centre for Advance Trade Research, Media & Corporate Communications. (2019, June 26). India largest producer & exporter of Turmeric in the world: TPCI [Press release]. Retrieved November 27, 2020, from https://www.tpci.in/press_release/india-largest-producer-exporter-of-turmeric-in-the-world-tpci/

- Chandan, S., Mohan, B. P., Chandan, O. C., Ahmad, R., Challa, A., Tummala, H., . . . Adler, D. G. (2019, November 29). Curcumin use in ulcerative colitis: Is it ready for prime time? A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Retrieved December 20, 2020, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6928475/

- Coelho, M. R., Romi, M. D., Ferreira, D. M., Zaltman, C., & Soares-Mota, M. (2020, July 31). The Use of Curcumin as a Complementary Therapy in Ulcerative Colitis: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Clinical Trials. Retrieved December 20, 2020, from https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/12/8/2296/htm

- Cowell, W., Ireland, T., Vorhees, D., & Heiger-Bernays, W. (2017, March 30). Ground turmeric as a source of lead exposure in the United States. Retrieved March 20, 2021, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5415259/

- Daily, J. W., Yang, M., & Park, S. (2016, August 1). Efficacy of Turmeric Extracts and Curcumin for Alleviating the Symptoms of Joint Arthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. Retrieved December 13, 2020, from https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/full/10.1089/jmf.2016.3705

- Dhakal, S., Schmidt, W. F., Kim, M., Tang, X., Peng, Y., & Chao, K. (2019, April 26). Detection of Additives and Chemical Contaminants in Turmeric Powder Using FT-IR Spectroscopy. Retrieved December 05, 2020, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6560428/

- Dixit, S., Purshottam, S. K., Khanna, S. K., & Das, M. (2009, September). Surveillance of the quality of turmeric powders from city markets of India on the basis of curcumin content and the presence of extraneous colours. Retrieved November 29, 2020, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/249066568_Surveillance_of_the_quality_of_turmeric_powders_from_city_markets_of_India_on_the_basis_of_curcumin_content_and_the_presence_of_extraneous_colours

- Dosoky, N. S., & Setzer, W. N. (2018, September 1). Chemical Composition and Biological Activities of Essential Oils of Curcuma Species. Retrieved November 30, 2020, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6164907/

- D’Ascola, A., Irrera, N., Ettari, R., Bitto, A., Pallio, G., Mannino, F., . . . Altavilla, D. (2019, October 24). Exploiting curcumin synergy with natural products using quantitative analysis of dose–effect relationships in an experimental in vitro model of osteoarthritis. Retrieved April 08, 2021, from https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2019.01347/full

- Ferreira, L. A., Henriques, O. B., Andreoni, A. A., Vital, G. R., Campos, M. M., Habermehl, G. G., & De Moraes, V. L. (1992, October 30). Antivenom and biological effects of ar-turmerone isolated from Curcuma longa (Zingiberaceae). Retrieved November 30, 2020, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1440627/

- Fujioka, S., Niu, J., Schmidt, C., Sclabas, G. M., Peng, B., Uwagawa, T., . . . Chiao, P. J. (2004, September). NF-kappaB and AP-1 connection: Mechanism of NF-kappaB-dependent regulation of AP-1 activity. Retrieved December 29, 2020, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC507000/

- Funk, J. L., Frye, J. B., Oyarzo, J. N., Zhang, H., & Timmermann, B. N. (2010, January 27). Anti-arthritic effects and toxicity of the essential oils of turmeric (Curcuma longa L.). Retrieved December 01, 2020, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2834817/

- General Introduction to the Chemistry of Dyes. (2010). In Some Aromatic Amines, Organic Dyes, and Related Exposures (Vol. 99, IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans). Lyon, FR: International Agency for Research on Cancer.

- Hadi, A., Pourmasoumi, M., Ghaedi, E., & Sahebkar, A. (2019, October 21). The effect of Curcumin/Turmeric on blood pressure modulation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Retrieved December 19, 2020, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31647981/

- Haidich, A. B. (2010, December 14). Meta-analysis in medical research. Retrieved December 13, 2020, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3049418/

- Han, S., Keum, Y., Seo, H., & Surh, Y. (2002, May). Curcumin Suppresses Activation of NF-κB and AP-1 Induced byPhorbol Ester in Cultured Human Promyelocytic Leukemia Cells. Retrieved December 29, 2020, from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/0541/e6a3f27d09cb1f0f1831657098361abb179e.pdf

- Hara-Kudo, Y., Ohtsuka, K., Onoue, Y., Otomo, Y., Furukawa, I., Yamaji, A., . . . Takatori, K. (2006, November 10). Salmonella Prevalence and Total Microbial and Spore Populations in Spices Imported to Japan. Retrieved December 09, 2020, from http://www.chromagar.com/fichiers/15501335900362_028x_69.10.2519.pdf

- Hayakawa, H., Minaniya, Y., Ito, K., Yamamoto, Y., & Fukuda, T. (2011, June 24). Difference of Curcumin Content in Curcuma longa L. (Zingiberaceae) Caused by Hybridization with Other Curcuma Species. Retrieved December 09, 2020, from https://www.scirp.org/html/5709.html

- Hesari, A. R., Ghasemi, F., Salarinia, R., & Azizabadi, H. (2018, June). Effects of curcumin on NF-κB, AP-1, and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in hepatitis B virus infection. Retrieved December 29, 2020, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325872088_Effects_of_curcumin_on_NF-kB_AP-1_and_Wntb-catenin_signaling_pathway_in_hepatitis_B_virus_infection

- Hu, C., Sheng, Y., Zhang, Q., Liu, H., Xie, X., Ma, W., . . . Dong, D. (2011, November 11). Curcumin inhibits herg potassium channels in vitro. Retrieved April 05, 2021, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22101212/

- Jain, R., Sharma, N., & Radhapyari, K. (2009). Removal of hazardous azo dye metanil yellow from industrial wastewater using electrochemical technique [PDF]. Athens: European Water Publications. Retrieved November 29, 2020, from http://www.ewra.net/ew/pdf/EW_2009_27-28_04.pdf

- Jhang, J., & Yen, G. (2017, November 13). The role of Nrf2 in NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Retrieved December 29, 2020, from https://www.nature.com/articles/cmi2017114

- Kellogg, J. J., Paine, M. F., McCune, J. S., Oberlies, N. H., & Cech, N. B. (2019, January 25). Selection and characterization of botanical natural products for research studies: A napdi center recommended approach. Retrieved February 08, 2021, from https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlehtml/2019/np/c8np00065d#cit5

- Kratz, J., Grienke, U., Scheel, O., Mann, S., & Rollinger, J. (2017, May 12). Natural products modulating the herg channel: Heartaches and hope. Retrieved April 05, 2021, from https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2017/np/c7np00014f#!divAbstract

- Kurien, B. T., Singh, A., Matsumoto, H., & Scofield, R. H. (2007, September 04). Improving the solubility and pharmacological efficacy of curcumin by heat treatment. Retrieved March 12, 2021, from https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/abs/10.1089/adt.2007.064

- Lasoff, D., Cantrell, F. L., & Ly, B. T. (2017, October). Death associated with intravenous turmeric (Curcumin) preparation. Retrieved April 05, 2021, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320309317_Death_associated_with_intravenous_turmeric_Curcumin_preparation

- Lee, B. S., Bhatia, T., Chaya, C. T., Wen, R., Taira, M. T., & Lim, B. S. (2020, March 16). Autoimmune hepatitis associated with turmeric consumption. Retrieved April 06, 2021, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7162126/

- Ling, J., Wei, B., Lv, G., & Ji, H. (2012, January). Anti-hyperlipidaemic and antioxidant effects of turmeric oil in hyperlipidaemic rats. Retrieved November 30, 2020, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/257163601_Anti-hyperlipidaemic_and_antioxidant_effects_of_turmeric_oil_in_hyperlipidaemic_rats

- Lombardi, N., Crescioli, G., Maggini, V., Ippoliti, I., Menniti‐Ippolito, F., Gallo, E., . . . Vannacci, A. (2020, July 20). Acute liver injury following turmeric use in Tuscany: An analysis of the Italian Phytovigilance database and systematic review of case reports. Retrieved April 05, 2021, from https://bpspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bcp.14460

- Madhusankha, M., Thilakarathna, C., & Navaratne, S. (2018, July). Analysis of curcumin content in Sri Lankan and Indian turmeric rhizomes and investigating its impact on the colour. Retrieved November 29, 2020, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326264303_Analysis_of_curcumin_content_in_Sri_Lankan_and_Indian_turmeric_rhizomes_and_investigating_its_impact_on_the_colour

- Mansouri, K., Rasoulpoor, S., Daneshkhah, A., Abolfathi, S., Salari, N., Mohammadi, M., . . . Shabani, S. (2020, August 24). Clinical effects of curcumin in enhancing cancer therapy: A systematic review. Retrieved December 18, 2020, from https://bmccancer.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12885-020-07256-8

- Monfoulet, L., Mercier, S., Bayle, D., Tamaian, R., Barber-Chamoux, N., Morand, C., & Milenkovic, D. (2017, July 22). Curcumin modulates endothelial permeability and monocyte transendothelial migration by affecting endothelial cell dynamics. Retrieved January 09, 2021, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28739530/

- Nasef, N. A., Loveday, S. M., Golding, M., Martins, R. N., Shah, T. M., Clarke, M., . . . Singh, H. (2019, July 26). Food matrix and co-presence of turmeric compounds influence bioavailability of curcumin in healthy humans. Retrieved March 30, 2021, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31347643/

- Nelson, K. M., Dahlin, J. L., Bisson, J., Graham, J., Pauli, G. F., & Walters, M. A. (2017, January 11). The Essential Medicinal Chemistry of Curcumin. Retrieved January 24, 2021, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5346970/

- Nelson, K. M., Dahlin, J. L., Bisson, J., Graham, J., Pauli, G. F., & Walters, M. A. (2017, May 11). Curcumin May (Not) Defy Science. Retrieved January 25, 2021, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5430405/

- Ng, Q. X., Soh, A. Y., Loke, W., Venkatanarayanan, N., Lim, D. Y., & Yeo, W. (2018, September 22). A Meta-Analysis of the Clinical Use of Curcumin for Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS). Retrieved December 14, 2020, from https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/7/10/298/htm

- Nogawa, H., & Kawai, T. (2011, November 11). Herg trafficking inhibition in drug-induced lethal cardiac arrhythmia. Retrieved April 05, 2021, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24998878/

- Oancea, P., & Meltzer, V. (2014, January). Kinetics of tartrazine photodegradation by UV/H2O2 in aqueous solution. Retrieved March 30, 2021, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/257908806_Kinetics_of_tartrazine_photodegradation_by_UVH2O2_in_aqueous_solution

- Patel, S. S., Acharya, A., Sargunam, R. R., & Agrawal, R. (2019, January). Cellular and molecular mechanisms of curcumin in prevention and treatment of disease. Retrieved December 12, 2020, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/330334241_Cellular_and_molecular_mechanisms_of_curcumin_in_prevention_and_treatment_of_disease

- Priyadarsini, K. I. (2014, December 1). The chemistry of curcumin: From extraction to therapeutic agent. Retrieved February 10, 2021, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6270789/

- Qin, S., Huang, L., Gong, J., Shen, S., Huang, J., Ren, H., & Hu, H. (2017, October 11). Efficacy and safety of turmeric and curcumin in lowering blood lipid levels in patients with cardiovascular risk factors: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Retrieved December 20, 2020, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29020971/

- Qiu, P., Man, S., Li, J., Liu, J., Zhang, L., Yu, P., & Gao, W. (2015, March 15). Overdose Intake of Curcumin Initiates the Unbalanced State of Bodies. Retrieved April 04, 2021, from https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jafc.6b00053

- Ranjan, A. P., Mukerjee, A., Helson, L., & Vishwanatha, J. K. (2013, December 14). Mitigating prolonged qt interval in cancer nanodrug development for accelerated clinical translation. Retrieved April 06, 2021, from https://jnanobiotechnology.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1477-3155-11-40

- Ringman, J. M., Frautschy, S. A., Teng, E., Begum, A. N., Montine, T. J., Cummings, J. L., . . . Cole, G. M. (2012, October 29). Oral curcumin for alzheimer’s disease: Tolerability and efficacy in a 24-week randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled study. Retrieved February 06, 2021, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23107780/

- Risk Profile: Pathogens and Filth in Spices [PDF]. (2017). Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved December 09, 2020, from https://www.fda.gov/media/108126/download

- Rodrigues, F. C., Anil, N., & Thakur, G. (2019, May). Developments in the Anticancer Activity of Structurally Modified Curcumin: An Up-to-Date Review. Retrieved March 11, 2021, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/333083417_Developments_in_the_Anticancer_Activity_of_Structurally_Modified_Curcumin_An_Up-to-Date_Review

- Roin, B. N. (2013, May 07). Unpatentable drugs and the standards of patentability. Retrieved March 07, 2021, from https://dash.harvard.edu/handle/1/10611775

- Sahebkar, A., & Henrotin, Y. (2015, December 12). Analgesic Efficacy and Safety of Curcuminoids in Clinical Practice: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Retrieved December 18, 2020, from https://academic.oup.com/painmedicine/article/17/6/1192/2240744

- Sahin, K., Pala, R., Tuzcu, M., Ozdemir, O., Orhan, C., Sahin, N., & Juturu, V. (2016, August 29). Curcumin prevents muscle damage by regulating NF-κB and Nrf2 pathways and improves performance: An in vivo model. Retrieved December 28, 2020, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5010171/

- Sangari, N. U. (2014, November). Enhanced Photodecoloration of Metanil Yellow Dye By ZnO in Presence of Beta Cyclodextrin in Aqueous Solution. Retrieved March 30, 2021, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277710229_Enhanced_Photodecoloration_of_Metanil_Yellow_Dye_By_ZnO_in_Presence_of_Beta_Cyclodextrin_in_Aqueous_Solution

- Sasikumar, B. (2019, December 30). Advances in adulteration and authenticity testing of turmeric ( Curcuma longa L.). Retrieved December 09, 2020, from http://updatepublishing.com/journal/index.php/josac/article/view/6072/5283

- Schneider, A., Hossain, I., VanderMolen, J., & Nicol, K. (2017, August). Comparison of remicade to curcumin for the treatment of Crohn’s disease: A systematic review. Retrieved December 19, 2020, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317692487_Comparison_of_remicade_to_curcumin_for_the_treatment_of_Crohn%27s_disease_A_systematic_review

- Sharifi-Rad, J., Rayess, Y. E., Rizk, A. A., Sadaka, C., Zgheib, R., Zam, W., . . . Martins, N. (2020, June 23). Turmeric and Its Major Compound Curcumin on Health: Bioactive Effects and Safety Profiles for Food, Pharmaceutical, Biotechnological and Medicinal Applications. Retrieved December 13, 2020, from https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2020.01021/full

- Singh, G., Kapoor, I. P., Singh, P., De Heluani, C. S., De Lampasona, M. P., & Catalan, C. A. (2010, January 21). Comparative study of chemical composition and antioxidant activity of fresh and dry rhizomes of turmeric (Curcuma longa Linn.). Retrieved December 01, 2020, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20096323/

- Singh, U., Verma, S., Ghosh, H. N., Rath, M. C., Priyadarsini, K. I., Sharma, A., . . . Mukherjee, T. (2009, December 02). Photo-degradation of curcumin in the presence of tio2 nanoparticles: Fundamentals and application. Retrieved March 31, 2021, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1381116909005469

- Singh, V., Jain, M., Misra, A., Khanna, V., Rana, M., Prakash, P., . . . Barthwal, M. K. (2013, August 28). Curcuma oil ameliorates hyperlipidaemia and associated deleterious effects in golden Syrian hamsters. Retrieved December 01, 2020, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23673139/

- Singh, V., Rana, M., Jain, M., Singh, N., Naqvi, A., Malasoni, R., . . . Barthwal, M. K. (2015, January 14). Curcuma oil attenuates accelerated atherosclerosis and macrophage foam-cell formation by modulating genes involved in plaque stability, lipid homeostasis and inflammation. Retrieved December 01, 2020, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25391643/

- Smith, T. J., & Ashar, B. H. (2019, January 9). Iron deficiency anemia due to high-dose turmeric. Retrieved April 06, 2021, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6414192/

- Smith, T., Gillespie, M., Eckl, V., Knepper, J., & Reynolds, C. M. (2019). Market Report – Herbal Supplement Sales in US Increase by 9.4% in 2018Record growth driven by sales of CBD, mushrooms, and immune-health products [PDF]. Austin: American Botanical Council. Retrieved November 28, 2020, from http://cms.herbalgram.org/herbalgram/issue123/files/HG123-HMR.pdf

- Tayyem, R. F., Heath, D. D., Al-Delaimy, W. K., & Rock, C. L. (2006). Curcumin content of turmeric and curry powders. Retrieved November 29, 2020, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17044766/

- Vallée, A., Lecarpentier, Y., & Vallée, J. (2019, July 22). Curcumin: A therapeutic strategy in cancers by inhibiting the canonical WNT/β-catenin pathway. Retrieved December 27, 2020, from https://jeccr.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13046-019-1320-y

- Vaughn, A. R., Branum, A., & Sivamani, R. K. (2016, August). Effects of Turmeric (Curcuma longa) on Skin Health: A Systematic Review of the Clinical Evidence. Retrieved December 17, 2020, from https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/12/8/2296/htm

- Vineeth, D., Venkateshwar, C., & Unnisa, S. A. (2014, January). TREATMENT OF CURCUMA LONGA (TURMERIC) CONTAMINATED WITH HEAVY METALS. Retrieved December 09, 2020, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301548339_TREATMENT_OF_CURCUMA_LONGA_TURMERIC_CONTAMINATED_WITH_HEAVY_METALS

- Wagner, H. (2010, November). Synergy research: Approaching a new generation of phytopharmaceuticals. Retrieved March 12, 2021, from https://www.academia.edu/2000104/Synergy_research_approaching_a_new_generation_of_phytopharmaceuticals?auto=download

- White, M. С, Pasupuleti, V., Roman, Y. M., Li, Y., & Hernandez, A. V. (2019, May 20). Oral turmeric/curcumin effects on inflammatory markers in chronic inflammatory diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Retrieved January 25, 2021, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31121255/

- Woo, J., Park, J., Jang, J., Yang, H., Surh, Y., & Na, H. (2020, November). Curcumin induces expression of 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase in gastric mucosal cells and mouse stomach in vivo: AP-1 as a potential target. Retrieved January 03, 2021, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32735936/

- Yuan, F., Dong, H., Gong, J., Wang, D., Hu, M., Huang, W., . . . Lu, F. (2019, September 1). A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials on the Effects of Turmeric and Curcuminoids on Blood Lipids in Adults with Metabolic Diseases. Retrieved December 20, 2020, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6743846/